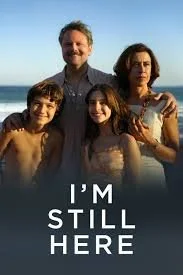

Episode 52: I’m Still Here (2024)

Guest: Isabela Amaral

Listen Anywhere You Stream

~

Listen Anywhere You Stream ~

I’m Still Here (dir. Walter Salles, 2024) is based on the true story of the enforced disappearance and murder of former congressman Rubens Paiva by the military dictatorship in Brazil. The film opens in Rio de Janeiro in 1970, where Rubens lives with his wife, Eunice, and their five children. Their lives are forever altered when the military government arrests and disappears Rubens. The film describes Eunice’s attempt to find out what happened to Rubens and to rebuild her life and raise her family in his absence. The film is based on the memoir of their son, Marcelo Rubens Paiva, who was a young boy when Rubens was disappeared. I’m Still Here provides a harrowing account of Brazil's military dictatorship and a moving story of a woman’s struggle to overcome adversity and obtain justice.

19:29 Exile as another tool of repression 23:08 Enforced disappearances

27:18 Leveraging international pressure

29:08 Eunice Paiva’s struggle and success

33:15 Support for the military dictatorship

36:01 Finally obtaining Rubens’ death certificate 25 years later

40:10 Brazil’s National Truth Commission 48:39 Authoritarian threats to democracy today

0:00 Introduction

2:16 The military dictatorship in Brazil

4:38 Living amid contradictions

6:52 The kidnapping of the Swiss ambassador

8:33 Rubens’ arrest and disappearance

12:38 Authoritarian legality 14:18 The arrest and mistreatment of family members 17:16 Covering up state crimes

Timestamps

-

00;00;15;25 - 00;00;43;10

Jonathan Hafetz

Hi, I'm Jonathan Hafetz, and welcome to Law on Film, a podcast that explores the rich connections between law and film, looking at how law influences film and film influences law. This episode we look at I'm Still Here at the 2024 film from Brazil, directed by Walter Salles. The film is based on the true story of the enforced disappearance and murder of former Congressman Ruben Paiva by the military dictatorship in Brazil.

00;00;43;13 - 00;01;09;16

Jonathan Hafetz

The film opens in Rio de Janeiro in 1970, where Rubens lives with his wife Eunice and their five children. Their lives are forever altered when the military government arrests Rubens and Eunice. The film describes Eunice's attempt to find out what happened to Rubens, and to rebuild her life and raise her family in his absence. The film is based on the memoir of their son, Marcello Rubens Paiva, who was a young boy when Rubens disappeared.

00;01;09;18 - 00;01;36;29

Jonathan Hafetz

I'm Still Here provides a harrowing account of the military dictatorship in Brazil, and a moving story of a woman's struggle to overcome adversity and achieve justice. I'm joined for this episode by Isabella Amaral, a PhD candidate at the State University of Rio de Janeiro. She's also a temporary lecturer in constitutional law at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, and a legislative advisor to the State Legislative Assembly of Rio de Janeiro.

00;01;37;01 - 00;01;41;24

Jonathan Hafetz

Isabella, welcome to LA on film. Great to have you on to talk about. I'm still here.

00;01;41;27 - 00;02;16;07

Isabela Amaral

Hi, everyone. Hi, Jonatan. And thank you so much for having me. I'm really excited to be here to talk about I'm Su Year, a film that has gained such incredible attention at the Oscars. And it's also a special conversation for me personally, because my PhD research focuses on artistic freedom and censorship. So I'm so glad we can have this conversation right now.

00;02;16;09 - 00;02;34;04

Jonathan Hafetz

Let's go back to 1970, which is when the film takes place in Rio de Janeiro. So during the military dictatorship in Brazil, at some years, and by this point, we have an opening shot just to let us know where we are. Right. You have a beautiful scene in one of the beautiful beaches in Rio, and there's a military helicopter flying over.

00;02;34;04 - 00;02;49;29

Jonathan Hafetz

I think it's Leblon beach. From what I've read. But anyway, so you've got these kind of jarring contrasts and can you give some historical context for this period? When did the military coup occur and why? And sort of what was happening in around 1970 when the film takes place.

00;02;50;01 - 00;03;36;27

Isabela Amaral

The military coup occurred in 1964, when the armed forces deposed President John Glass under the pretext of preventing a communist threat. In the 70s, the regime was at the peak of repression, the institutional way back to number five. That was a type of decree. It was issued by the military government in December 1968. It's officially suspended. Civil rights shut down Congress, censored the press, and even abolished shared habeas corpus in political cases.

00;03;36;29 - 00;04;16;03

Isabela Amaral

But repression wasn't limited. Said to politicians like Corbyn's, striking case was that of the musician Shikoku Blackie, who really said this song up is a direct critique of the regime. The song initially played on the radio, but was quickly censored. And from then on, everything she tried to release was blockades. He even created a pseudonym, junior she Delay due to to his songs past the censors.

00;04;16;07 - 00;04;37;07

Isabela Amaral

These episodes shows how the dictatorship tried to control not only politics, but also art and cultural life. And I think that's the the context of the military coup and the the regime in general when the film takes place.

00;04;37;10 - 00;04;59;13

Jonathan Hafetz

You know, it's interesting that you talk about the sort of way it conflicted with the artistic life and freedom of expression and artistic expression and sort of what the context was. Right. Where it's 1970, sort of the 1960s counterculture. And that's sort of in full swing, at least in a big city like Rio de Janeiro. And so we see a lot of normal activities, too.

00;04;59;14 - 00;05;19;04

Jonathan Hafetz

So that's one of the things, I think so great about this film. One of the first shots is we see kids playing volleyball at the beach. We see other activities like the family getting ice cream together, and we also see signs of the military government, the military vehicles around Rio. Does it capture what life was like in 1970s with all these kind of really competing?

00;05;19;05 - 00;05;24;10

Jonathan Hafetz

You've got the military dictatorship, but you've also got the 1960s counterculture and full swing.

00;05;24;12 - 00;06;01;26

Isabela Amaral

Yes, yes. It captures it very well. Brazil leaves in contradiction. On one hand, there seemed to be normal life beaches, families eating ice cream, the 70s World Cup, a sense of prosperity. You tie it to the economic miracle. On the other, it was also the the peak of what Brazilian journalist Elio Gaspar called the jittery conqueror that the open dictatorship, a period of maximum repression.

00;06;02;01 - 00;06;42;07

Isabela Amaral

Celso shapes arbitrary arrests, tortures, disappearances. This coexistence of calm daily life and brutal political violence was one of the of the defining features of Brazil in the 70s. And the film captures another crucial element the sense of fear that hung in the air. Even in ordinary moments, there was always the risk that the police or the military could show up, break the normality and turn daily life upside down.

00;06;42;13 - 00;07;03;12

Jonathan Hafetz

Which I mean is essentially right. What happens with Rubens's family? Right. I mean, it's exactly what happens. It's just interrupted. That's one of the central things in the film, and you know, it starts out in terms of the larger events. What triggers the crackdown when development triggers the crackdown, at least in the film, is the kidnaping of the Swiss ambassador.

00;07;03;14 - 00;07;17;14

Jonathan Hafetz

Also, there had been the kidnaping of the U.S. ambassador to Brazil. Just another film about that the year before. So how significant were these events and how did they kind of contribute to what was happening in Brazil at that time?

00;07;17;17 - 00;08;03;16

Isabela Amaral

The kidnaping of Swiss Ambassador and 70 was highly significant because it exposed Brazil's political tensions to the world. The year before, like you said, 69 US Ambassador Charles L break had also been kidnaped. These actions were strategies of armed leftist groups to pressure the dictatorship into releasing political prisoners. It wasn't something that happened often, but when it did, it had huge national and international repercussions.

00;08;03;18 - 00;08;19;12

Isabela Amaral

The effect was, I think, twofold. On one side, it drew attention to the regime's abuses. On the other, it gave the government an excuse to intensify repression.

00;08;19;15 - 00;08;40;06

Jonathan Hafetz

Yeah, we see in the film they sort of intensification, this repression. We see it on one level where one of Ruben and Eunice's daughter thinks their oldest daughter is out with friends, and there there's a military checkpoint, and they're stopped. They're harassed. And then we also see the intensification that leads to Ruben's arrest. Right. Which becomes the central action in the film.

00;08;40;06 - 00;09;01;27

Jonathan Hafetz

And and so the film shows Ruben seizure and disappearance. I don't want to use. I mean, the word arrest is loaded because he's not actually really arrested in any formal legal sense. Instead, it's a group of men armed in plain clothes with no identification, show up at Ruben's home. He lives in a, you know, a very nice middle, upper middle class area by the beach.

00;09;01;29 - 00;09;21;23

Jonathan Hafetz

They show up at his home and they tell him they need to take him in for questioning. No charges. No information is given to Rubens or to his family. And Rubens, we later learn, he's been taken to a military barracks in the city, held without access to a lawyer or a judge, and tortured. So what were some of the circumstances behind Ruben's arrest?

00;09;21;23 - 00;09;30;01

Jonathan Hafetz

And this is based on a true story based on, you know, what actually happened? So what were some of the circumstances and how typical was what happened to Rubens?

00;09;30;03 - 00;10;17;20

Isabela Amaral

Well, Rubens was arrested because we represented exactly the kind of figure the dictatorship wanted to neutralize. A former congressman, a lawyer for political prisoners, someone we have legitimacy to give voice to disarms. He is raised. Illustrates what political scientists call authoritarian legality. The regime didn't see itself as outside the law. Instead, it created institutional acts, decrees imposed by the executive above the Constitution that gave arbitrary actions and an appearance of legality.

00;10;17;27 - 00;11;00;02

Isabela Amaral

E5, for example, while our arrest is without judicial order, the closing of Congress and the suspension of rights. So the government didn't need formal charges. It was enough to label someone, subversive a communist collaborator like Rubens. And unfortunately, it was pretty typical arbitrary arrest, torture and disappearances were systematic practices of the dictatorship. People were taken from their homes by armed men without judicial orders, and many never came back.

00;11;00;04 - 00;11;44;15

Isabela Amaral

Another very emblematic case was that of journalist Vladimir Herzog. In 1975, he was assumed to testified at a military barracks in Sao Paulo, and a few hours later was found dead. The regime released a staged photo to suggest he had committed suicide, but no one believed it. The case had enormous impact. It's a ladder to a huge religious service in Sao Paulo's Catedral and became a, turning point in exposing the dictatorships practices.

00;11;44;18 - 00;12;05;22

Isabela Amaral

Hazard's case showed that repression didn't only target armed militants, but also journalists, artists and professionals who dared to question the regime. Ruben's disappearance fits into this wider pattern.

00;12;05;27 - 00;12;38;11

Jonathan Hafetz

Yeah, it's such an important point to underscore that, as you did, the fact you have a, you know, like with the journalist or with Rubens, a former congressman. So these are prominent people. I mean, to me, it suggests, you know, how confident and assertive the military would be, the military dictatorship and how brazen in its approach. And it also would have, I think, probably like a chilling effect, right, in ways that a rest of so-called ordinary citizens would not have quite the same effect is really multiplied when you see the military go after these very kind of prominent public figures.

00;12;38;13 - 00;12;59;23

Jonathan Hafetz

The other thing that I think your comment brings out is there's a line in the movie where Eunice, Rubens's wife asks, how could this happen in a country with, quote, a supposedly functioning justice system? And I think that's one of the things that's so striking about the movie is probably for many people, the justice system probably was functioning the way it always had.

00;13;00;02 - 00;13;05;09

Jonathan Hafetz

But there was this other sort of system that you kind of described.

00;13;05;11 - 00;13;42;27

Isabela Amaral

About the law system, the pleasure to see of the regime. I think the Brazilian dictatorship leaned heavily on what scholars call authoritarian legality, unlike Argentina or Chile, which rely more on extrajudicial violence or military decrees. Brazil systematically built a legal framework to give repression a formal cover. The latest example is the introduction of institutional work to number five that I told you.

00;13;42;29 - 00;14;19;00

Isabela Amaral

But there is a lot of cases beyond that. The regime adopted existing structures like the Department of Censorship to institutionalize the control of music, theater, film. In other words, the regime didn't say it was outside the law. It created the law to justify repression. That's why even arbitrary arrests like Rubin's appeared. The legal literacy system manipulated by the military.

00;14;19;02 - 00;14;43;26

Jonathan Hafetz

So after Rubens is arrested or taken to the barracks, Yunis, his wife and their daughter, one of their daughters, Eliana, are also brought in for questioning by the military. They're handcuffed, blindfolded as they're driven to the building. The military is using for its detentions and interrogations. The barracks in the city. Yunis is not charged with the crime or, given a lack, any access to a lawyer legal process.

00;14;43;28 - 00;15;00;09

Jonathan Hafetz

But we see her interrogation. But we don't really see Ruben's. We just have to imagine it. She's forced. Yunis is forced to look in a book with photos or headshots to say who she recognizes. The room is dark. They don't show any torture. But instead you hear it and you see it. There's blood on the floor. You see evidence of it.

00;15;00;15 - 00;15;22;26

Jonathan Hafetz

There's blood on the floor, presumably, of someone who was tortured in the room before her. And you can hear she can hear people crying out in pain from the other rooms. Yunis is not given any information about what's happened to her husband beyond vague insinuations about associating and helping communists and terrorists in exile. You know, she's held in abysmal conditions for 12 days before she's finally released.

00;15;23;01 - 00;15;41;16

Jonathan Hafetz

Her daughter is released after a day. But even then, the nonstop surveillance of Yunis in her home and her family continues. So what does this tell us about what happened to Yunis in particular? I mean, how common were these tactics to arrest or take in and interrogate family members in this way?

00;15;41;18 - 00;16;27;07

Isabela Amaral

They were common because repression wasn't only about silencing militants. It was also about breaking their families, wives, children, siblings were often taken in for questioning without charges to instill fear and psychological pressure. One powerful example is Clarice Herzog, the widow of the journalist Vladimir Zogg. She and her children lived under constant surveillance and intimidation after his death. Families were often wiretapped, harassed, or forced to testify.

00;16;27;12 - 00;16;54;05

Isabela Amaral

Their effect was to turn everyday life into a state of fear where everyone felt. Watch! Hear that? In Elise's case, being taken along with her diary showed exactly this tactic is spreading terror beyond the main targets, extending repression into the families fear.

00;16;54;07 - 00;17;12;05

Jonathan Hafetz

And they don't show it in the they don't really show it in the film so much, but presumably in other cases, right. What happens is not just in the family, but the neighbors. Right. See where this person go, right? They disappeared for ten days, right? And that spreads the fear as well. It's a multiplier effect.

00;17;12;08 - 00;17;16;09

Isabela Amaral

Yeah. Neighbors, friends. It's very common.

00;17;16;12 - 00;17;48;09

Jonathan Hafetz

The other thing I thought was notable was what? The military's response. Right. They then spread. They spread false information. You got disinformation that Rubins was freed or had been freed by armed insurgents and fled the country. At the same time, the military government refuses to acknowledge they had anything to do with this disappearance. So how were disinformation and secrecy used as a sort of another tool in the box of this, you know, authoritarian regime?

00;17;48;11 - 00;18;27;06

Isabela Amaral

Yeah, I think the dictatorship was a master at using lies as a political strategy. When someone was arrested, the government often simply denied it, saying the person had fled, was hiding, or had left the country. In humans case the they spread the story that he had been rescued by jailers and taking them taken abroad. Another emblematic example was again Vladimir Ezike.

00;18;27;08 - 00;18;40;01

Isabela Amaral

The regime is it staged a forum to claim he had committed suicide in jail, a lie that backfired and helped to steer up the opposition.

00;18;40;03 - 00;18;52;06

Jonathan Hafetz

And I'm thinking back, the tactics that you, you know, sort of described are, you these are 1970 tactics. I mean, the tactics now, the regimes have now are so much more sophisticated and penetrating and the, you know.

00;18;52;08 - 00;19;29;17

Isabela Amaral

Relation there is another case, reports and the historical studies also indicate that news about the 70s meningitis outbreak were censored to avoid the messaging, the regime's image of progress. In short, I think secrecy and disinformation weren't accidental. They were central tools of authoritarian control to keeping families trapped in uncertainty and cutting off the possibility of justice.

00;19;29;20 - 00;19;57;18

Jonathan Hafetz

And the response of some families, including even within Reuben and Eunice's family, was to leave. Right. So before Reuben's is disappeared. But as the you know, it's in the military dictatorship and their tensions are growing. One of their daughters, Moroka, their elder daughters, moves to London with family friends. Right. So how common was it for Brazilians, or at least for middle upper middle class Brazilians who had the ability to do so to to leave the country?

00;19;57;20 - 00;20;39;09

Isabela Amaral

It was fairly common, especially among artists, artists, intellectuals and students. Many left because they were threatened, and others were freed from prison in exchange for kidnapings ambassadors and some chose exile to continue their activism safely. Well-known examples include Caetano Veloso and You Back to Jail. Were were jailed and then forced into exile in London. The educator Paulo Ferretti spans nearly two decades abroad.

00;20;39;11 - 00;21;10;24

Isabela Amaral

Exile was not just an individual escape. It's also drained Brazil culturally and politically. For the regime, it was use of food to remove, remove inconvenient voices while keeping watch over their families and networks at home. In this way, exile became another tool of repression, making clear that there was no space for Desam in Brazil.

00;21;10;26 - 00;21;20;02

Jonathan Hafetz

So it sounds like the military would to some extent allow or even potentially encourage some people to leave, as opposed to, say, shutting the borders down.

00;21;20;04 - 00;21;44;21

Isabela Amaral

Yeah, I think the regime encourage people to go out because it's better for a regime. There is a little bit lower dissent. And, the regime, it's good for the regime. Everybody that don't agree with the regime go back and exile and that's it.

00;21;44;23 - 00;22;03;05

Jonathan Hafetz

And it's interesting too, that you can see in the film, I mean, again, Rocha, their daughter, flees before Rubens is disappeared. But there's this sort of debate, right, that people are having. I'm sure it occurred in many homes in Brazil at the time. Right. Whether or not to go, how long to wait. And, you know, ultimately, you know, they do agree to allow her to go.

00;22;03;05 - 00;22;17;20

Jonathan Hafetz

But that dynamic is sort of captured because I think probably for people, especially people who are perhaps, maybe a, you know, a little less active or prominent than Rubens about whether or not, of course, or maybe those people too, whether it was time to go right, or do you need to leave, or can you still stay?

00;22;17;22 - 00;22;53;13

Isabela Amaral

It's a difficult question. I, I don't know, I have a good answer for that. But the people don't know the they don't know when it's better to zero stay here. It's a difficult decision because there is a lot of families, everybody friends and home and just, middle class and upper classes have, money to vacations or to exile, and it's a problem.

00;22;53;16 - 00;23;11;03

Jonathan Hafetz

Yeah. We even seen with Veronica when she realizes, kind of what's happened. Right. And we'll talk about the mystery around what happened to Rubens. But. And when she should realize it, and she comes home. So even after despite the repression, she. Because she needs to be back with her family. So let's talk a little bit more about forced disappearances.

00;23;11;06 - 00;23;34;16

Jonathan Hafetz

There's a line in the movie from Eunice saying forced disappearances were one of the cruelest acts of the regime, because you kill one person and condemn all the others to eternal psychological torture. So why are they so devastating? And, what makes their status of forced disappearances, a crime under international law?

00;23;34;19 - 00;24;16;29

Isabela Amaral

I think they are devastating because they don't. And with the initial act, the doubt, the the absence of a body and the denial of truth makes the pain last longer. Families are trapped in the cycle of not knowing, unable to, to mourn or move forward. It's not just one life taken. It's, entire family condemned to live with permanent psychological torture and fathered disappearances are considered among the worst human rights violations.

00;24;16;29 - 00;25;07;14

Isabela Amaral

In 2006, the United Nations adopted convention specifically on this issue, defining down as crimes against humanity when carried out systematically. What makes them especially cruel is that they are a continuing crime. The violence doesn't end with the arrest or death. Families leave without answers, without the body, without the right to mourn. It is exactly the devastating and enduring nature of this form of violence that makes forced disappearances such a central concern of international law, which classifies then these crimes against humanity.

00;25;07;18 - 00;25;22;04

Isabela Amaral

When systematic prohibits their amnesty, and imposes on the states a duty to investigate, prosecute and provide reparations to victims and their families.

00;25;22;07 - 00;25;40;29

Jonathan Hafetz

I think the film really shows you this impact and it takes you through, and we can see in the beginning, right where we really don't know, right. What's happened. You know, initially, after, rulings is taken and even after he's been gone and Eunice comes in, they really don't know. He might just be in a prison somewhere.

00;25;41;01 - 00;26;03;28

Jonathan Hafetz

And, so. And one of the first battles Eunice has to wage is to get to even acknowledge that the government had arrested Ruben's right. I mean, that's it's that's what's. So the secret arrest. And so with the help of a lawyer friend or a friend, she files a habeas corpus petition. What are some of the obstacles Eunice faces?

00;26;03;28 - 00;26;09;09

Jonathan Hafetz

And what role does the habeas petition play in this context?

00;26;09;11 - 00;26;48;29

Isabela Amaral

Habeas corpus exists exactly to protect against arbitrary detention. It requires that anyone arrested be brought before a judge. But after I five habeas corpus was suspended in political cases. So whenever you need a few petitions to locate who bends, the courts either claimed lack of jurisdiction or simply refused to hear them, it was like knocking on the door you knew was locked, even so, these petitions mattered.

00;26;48;29 - 00;27;19;13

Isabela Amaral

Symbolically. They kept the fight alive, showed that there was his existence in the legal sphere, and exposed the regime's manipulation of the law. They also mattered because acknowledgment itself was crucial. Forcing the state to admit Ruben's had been detained was the first step toward breaking the wall of of denial.

00;27;19;15 - 00;27;48;12

Jonathan Hafetz

One other tool that, Eunice and her friends and supporters use is to try to get international attention. I'm Rubens's disappearance, and his case does get a great deal of attention. Right? Their daughter Veronica. Right. Who's in London? That's how she knows all about it. She says it's, you know, it's all over the news, right? And so, I guess, as a strategy, how did advocates and victims seek to leverage international pressure and did that have any kind of effect on the military government?

00;27;48;15 - 00;28;23;00

Isabela Amaral

I think international pressure was a key weapon for families, families, lawyers and human rights groups took cases like whole to the United Nations and the Organization of American States, but they also relied heavily on the the for foreign press, the kidnaping of ambassadors, for example, for said the regime of to to free political prisoners who then gained visibility abroad.

00;28;23;03 - 00;29;08;28

Isabela Amaral

People like Fernando Gambetta and Jose Seal became well known. Internationally exiled artists like katana NGO also used their platforms in Europe to denounce repression. This network of of external accusations undercuts the dictatorships image of modernity and progress, and it had a real impact. Each embarrass had Brazilian authorities generated critical reports from international bodies and gave moral support to those resisting inside the country.

00;29;09;00 - 00;29;30;09

Jonathan Hafetz

One of the key moments, I mean, perhaps a key moment in the film, perhaps a key moment in the film, comes when Eunice learns from Ruben's inner circle that he had been killed. Right. So they know. So she finds out, it's a it's a wild, you know, but but but relatively early on in terms of the longer story that he's been killed, they don't have any details.

00;29;30;16 - 00;30;06;04

Jonathan Hafetz

They don't know how or where he died. The military still won't admit they had him in custody. And so at that point, that's sort of a turning point for Eunice, right? And just because she has to rebuild her life, and her family's life, without Ruben's, So how does she respond to these, personal and material, including financial challenges and, you know, and are there sort of broader messages about how families had to cope, when faced with the disappearance of a of a loved one?

00;30;06;07 - 00;30;46;13

Isabela Amaral

I, I think, I guess uneasy faces that the brutal absence of who bangs while raising her children alone, instead of retreating into private grief, she reinvented herself. She went back to school, earning her law degree, to teach for seven, and became a respected human rights lawyer working with families of disappeared. And also in the of indigenous people peoples.

00;30;46;15 - 00;31;13;20

Isabela Amaral

Her journey shows how how she turned personal tragedy into political and social strength for her surviving man. He builds in everyday life while insisting on the fight for memory and justice, not just for who bends a yes, but for all who's suffered under the dictatorship.

00;31;13;22 - 00;31;32;10

Jonathan Hafetz

Yeah, I think that's really well. And and I should say, you know, Eunice was, I'd say upper middle class or fairly affluent, educated and although, you know, she had five children and then it was a struggle, she in some sense had certain advantages that other people might not have. But even so, despite the fact that she grabbed resources, everything was challenging.

00;31;32;10 - 00;31;59;21

Jonathan Hafetz

There's that one scene where she goes to the bank and she tries to take out money that she needs, and because of, I think it's a joint account. So there was a requirement of her husband's signature, or maybe that was a law and or Brazil, dual nature of financial, family, financial relations. Whatever it is, she can't get the money even though the bank agent who you know, knows her well knows that Rubens has been disappeared.

00;31;59;23 - 00;32;23;11

Isabela Amaral

Yeah it is. It truly stands as an example of struggle and perseverance in the face of very difficult circumstances. And this example of bank is a good example of the situation of every family who had a person who disappeared in a dictatorship.

00;32;23;13 - 00;32;40;07

Jonathan Hafetz

There's another scene which I want to ask you a little bit more about. One of the early scenes. We see it before anything has happened to Rubens in unison. Their family. But it is that the military dictatorship seems like a shadow. Right? You see them going out? Probably a weekend with the family. They're having ice cream in an ice cream parlor.

00;32;40;12 - 00;33;04;15

Jonathan Hafetz

Life is proceeding very normally. Right, I found it, you know, in the most powerful moments in the movie was when they go back after Rubens has disappeared. And I think at this point, Eunice knows he's been killed yet doesn't really told her family. But they're back and it just the scene feels very different. She knows she can no longer pretend that there's any kind of normalcy, and yet life does go on.

00;33;04;15 - 00;33;24;12

Jonathan Hafetz

It's seemingly pretty normal for probably everybody else, you know, in the ice cream shop or they've they've adjusted, they've made their peace to some extent, or they're living under the dictatorship. So how much if not active support, passive support for, you know, did the military dictatorship have during this time? Because it seems like, you know, a lot of people did kind of go on.

00;33;24;12 - 00;33;28;06

Jonathan Hafetz

And for them, life proceeded fairly normally much of the time.

00;33;28;08 - 00;34;06;05

Isabela Amaral

I think at the start the regime had considerable support, especially from the urban middle class business sectors and the parts of the media. Many believed the military had saved the country from communism and brought stability to the country. Support was also fueled by the economic miracle. Fast growth in the late 60s and early 70s. But it wasn't just passive acceptance.

00;34;06;07 - 00;34;52;05

Isabela Amaral

Some sectors called for these repression. Conservative groups that defended censorship denounced neighbors or teachers as subversives and never organized violent actions like the communist hunters, which started with a theater performance of the Viva by Shook Back and the. In this episode, they violently attacked the cast on stage and vandalized the theater, and one of the actresses, Maria Pareto, later recalled that the violence was met with indifference and even approval from parts of the audience.

00;34;52;07 - 00;35;35;16

Isabela Amaral

Instead of helping. Some people said the attack was well deserved, as a lesson for those who dared to challenge morality and good customs. So the dictatorship was sustained not only by military force, but also by collaboration from parts of society. And these continuity matters, decades later, some of these same conservative sectors reemerged in their support for Bolsonaro, echoing old patterns of backing authoritarian leaders who promised order.

00;35;35;19 - 00;35;55;22

Jonathan Hafetz

That such helpful background and the movie kind of does really get into all that, but I feel like it sort of sums it up. There's one line where Eunice is being interrogated by the military interrogator when she's at the barracks, and one of the things he tells her about why she's in custody is he tells her, you know, we're trying to preserve and protect your way of life so you can continue your life.

00;35;55;25 - 00;36;20;12

Jonathan Hafetz

Seeing your friends playing backgammon. And that sort of encapsulates, to some extent, what you're saying. So the film after the first part, the longest part is the disappearance of Ruben's the realization that, you know, he's learning from friends that he's been killed and then having to rebuild. And so this sort of first part ends with the family packing up the car and moving to Sao Paulo, saying goodbye to Rio.

00;36;20;14 - 00;36;47;11

Jonathan Hafetz

We then jump forward in time to 1996. So we're now 25 years later. By then. As you mentioned, Eunice is a successful human rights lawyer, and she finally obtains a death certificate from the state. At this point, the military dictatorship has ended, and this is the first acknowledgment that her husband had been killed. So what happens in this period kind of go from 1970 1996?

00;36;47;19 - 00;36;57;28

Jonathan Hafetz

Why and how does the military dictatorship end? And then also, why is this it? It's so important, even though Eunice is known to have been killed for 25 years.

00;36;58;01 - 00;37;31;02

Isabela Amaral

I think in this period, Brazil went through huge political changes after the height of the repression, the peak of the repression. The regime began, a slow political opening in in the 70s. In 1979, the amnesty law, along with exiles and political prisoners to return to Brazil, but also shielded military officials accused of torture and murder and disappearances.

00;37;31;04 - 00;38;11;09

Isabela Amaral

In 1985, after more than two decades without free presidential elections, Tancredo Knives was indirectly chosen as president, and after his death, Usani assumed office, marking the official end of the dictatorship, and in 1988, Brazil adopted a new democratic constitution, but for illness. This timeline meant something different. Through all these political shifts, she was still fighting the state's silence.

00;38;11;11 - 00;38;56;28

Isabela Amaral

Only in 1996, more than 25 years later, did she finally obtain an official death certificate for once prove he had been killed in military custody. The gap between Brazil's celebrated political transition and the reality to of families like hers is a stark democracy returned. But the truth came only in fragments much later. And I think the certificate is so significant because it was the first official acknowledgment by the Brazilian state that humans had been killed in custody.

00;38;57;00 - 00;39;30;17

Isabela Amaral

And when he she had known for decades, but without an official records, the family lived in a kind of limbo with no documentation, with no rights to properly mourn. Like. Like I said, the certificate didn't bring her bones back, but it ended the institutional lie that waited on the family daily for illness. It was a really. Finally, they state admitted what it had denied for 25 years.

00;39;30;17 - 00;39;45;24

Isabela Amaral

Collectively. It's also, symbolizes hope. It shows that other families of the disappeared, that that persistence could eventually force the truth out of silence.

00;39;45;26 - 00;40;01;16

Jonathan Hafetz

Yeah. And the film captures it's sort of, it's I don't want to say celebration, but it's bittersweet. But there is they there is a there's a sense of relief. Right? When they have it, the family goes, there's a news event around it. There's even like, she has a scrapbook. Eunice has a scrapbook and puts the certificate in.

00;40;01;16 - 00;40;22;17

Jonathan Hafetz

And then there's like a central closing of the book. They can finally only now closed this particular have some closure on that period. What happened? The film, though, doesn't end there. Right? So we've got this jump forward to 2014 again. So almost 20 years later at this point, Eunice is elderly, wheelchair bound. She's suffering from Alzheimer's disease.

00;40;22;19 - 00;40;52;10

Jonathan Hafetz

The family, they're all together. It's a larger extended family. Eunice is watching television sort of from inside. Everyone is outside having lunch, and she sees this report of the Truth Commission describing the atrocities committed by the military dictatorship. And the report mentions Rubens's case. He's described as an icon or one of the icons of the resistance. And despite her mental state, Eunice appears to recognize him and to remember the past starts to come back.

00;40;52;10 - 00;41;03;27

Jonathan Hafetz

It appears so. What's happened now, right in this next sort of period of time, from 1996 to 2014. And what was the Truth and Reconciliation Committee in Brazil.

00;41;03;29 - 00;41;59;07

Isabela Amaral

And and 2014, Brazil completed the work of the National Truth Commission, established in 2012, to investigate the dictatorships crimes. It was historic because the state officially recognized that tortured executions and disappearances had been state policy, not isolated excesses. The Commission documented 434 killed and disappeared, including five whose case was highlighted as emblematic. The commission had no power to punish, but it played a crucial role in giving visibility, gathering evidence and restoring dignity to victims and families.

00;41;59;07 - 00;42;22;23

Isabela Amaral

For see Dan, elderly and You seem who Bain's name acknowledged nationally was the confirmation of a lifelong struggle for Brazil. It was a call to memory, a reminder that democracy is rooted in suffering and at that same time, resistance.

00;42;22;25 - 00;42;43;29

Jonathan Hafetz

And so we, you know, it seems we have, with the individual acknowledgment of Rubens through the death certificate in 1996 and then through the findings society wide, if you will, of the Truth Commission about what happened, the disappearances of Rubens and others torture. But we do have seem to be kind of a divergence which you've touched on between the sort of truth and the acknowledgment.

00;42;43;29 - 00;43;13;08

Jonathan Hafetz

Right, the work of the Truth and Reconciliation Committee. And then what we often think of as other forms of accountability that is holding, you know, individuals responsible, typically through criminal prosecution for, what were crimes of murder or extrajudicial detention, torture. And so the film does at the end, for example, that while the Brazilian government admitted Rubens had been murdered in the army barracks in July 1971, that five officials had been charged, none had been arrested or punished.

00;43;13;11 - 00;43;32;26

Jonathan Hafetz

And this is, I think, emblematic on that. I've kind of what happened in Brazil, in contrast to, say, Chile and Argentina, where you had not just truth and reconciliation, but you had accountability in terms of, you know, criminal prosecutions. So, yeah, I just wonder if you could talk about that split in Brazil's overall approach to accountability.

00;43;32;28 - 00;44;10;11

Isabela Amaral

I think in Brazil we have, a problem of accountability because the 1975 amnesty law was framed as national reconciliation and not as accountability to the crimes and everything. It's allowing exiles and political prisoners to return, like I said. But at the same time, it also granted impunity to state agents responsible for torture, murder and disappearances. In 2002.

00;44;10;11 - 00;44;51;27

Isabela Amaral

And Brazil's Supreme Court upheld this interpretation that same year. However, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights ruled that such crimes are crimes against humanity and cannot be mislead, so we leave with a contradiction. Internationally, Brazil must investigate and punish. Domestically, the amnesty still blocks prosecutions. This institutional silence is part of why Bolsonaro could, decades later, openly celebrate the Q and honor torturers like Colonel Oostra.

00;44;51;27 - 00;45;25;12

Isabela Amaral

The legal shield means the past was never fully confronted, leaving space for authoritarian nostalgia to flourish. And this this is the same silence that helps explain why Bolsonaro himself could more recently attempt a new coup. He is trial for trying to subvert democracy shows that the past is never really past. When impunity prevails, authoritarianism finds new ways to return.

00;45;25;14 - 00;45;51;22

Jonathan Hafetz

It does it? I mean, I think there's even a there's even a connection I think to is US President Trump, who's been applying tremendous pressure on Brazil before Bolsonaro was convicted, you know, not to prosecute him and not to do that. And, and but in a sense, to me, that's exactly I have a magic of what you're saying, where we've had no real accountability for Trump's attempt to overturn through violent means, support the ballot means the outcome of the 2020 presidential election.

00;45;51;22 - 00;46;12;18

Jonathan Hafetz

So it's no accounting. The you trying to undermine accountability in Brazil? It's interesting because my understanding is the fact that he was convicted and sentenced is, in that sense, it's a break or a different path than the way that what happened in the military, the military dictatorship. But again, in, in Bolsonaro, as I understand that there's also calls now for amnesty as well.

00;46;12;18 - 00;46;14;24

Jonathan Hafetz

And that's sort of something that's on the table.

00;46;14;27 - 00;46;57;15

Isabela Amaral

I think the military regime has, centralized in the armed forces, especially the presidency, which ruled by decree two institutional acts. And now we have a democratic constitution. So the current authoritarianism and the current democratic erosion is part of institution of how institutions remain formally intact under the 1988 constitutions. But, have space for this type of movement of authoritarian practice.

00;46;57;15 - 00;47;29;13

Isabela Amaral

And I think now we have authoritarian practices that emerge not from a complete rapture, from a coop, but through erosion from we've seen such as pressures on the judiciary, manipulation of information, fake news and the legitimization, of the electoral process and there is a difference, but I think the nature is the same.

00;47;29;16 - 00;47;38;23

Jonathan Hafetz

I wonder how the film was received in Brazil in terms of what it's grappling with, in terms of Brazil's past and how it speaks to, to some extent, the present moment.

00;47;38;25 - 00;48;21;17

Isabela Amaral

So critics and human rights advocates received it very warmly because it centers, a emblematic case and foregrounds illnesses. Perhaps at the same time, parts of the rights mobilizes boycotts and the claim it's the film is is rewriting the past that polarizes the reception. It shows how the memory of the dictatorship is still contested. For some, the film is historical justice, for others, it's reopening wounds they'd rather keep closed.

00;48;21;24 - 00;48;26;26

Isabela Amaral

I think we have, a polarized reception in Brazil.

00;48;26;29 - 00;48;45;07

Jonathan Hafetz

And opening up the things for discussion about what actually happened in the past, the past kind of being contested, maybe given events around the world. But in Brazil and the United States, I mean, it seems a very timely film. You know, if you could summarize what's the message that the film offers in terms of where we are collectively today?

00;48;45;10 - 00;49;26;23

Isabela Amaral

It's a difficult question. Where are you are right now? We have, at the same time, a constitution in Brazil that is a democratic constitution that we have, constitutional rights, we have institutions that preserve democracy. But at the same time, this idea of authoritarianism is in the moment of power with Bolsonaro. And we have the right in the Congress, not in the executive right now, because we have the president Lula, but in the institutions.

00;49;26;23 - 00;49;42;27

Isabela Amaral

And we have and the Parliament. We have a lot of power to. Right. And I think it's, repercussion of these type of movements of authoritarianism. And that's the it's I think.

00;49;43;00 - 00;50;24;12

Jonathan Hafetz

I can say for, for me as a viewer, having seen this film recently, it would have registered very different for me ten years ago, you know, certainly before 2016 and maybe even since, and certainly before more recent events, you know, it certainly would have been powerful and would have been powerful understanding of what happened in Brazil. But, you know, as someone you know, viewing this, you know, in the United States in 2025, it really has it really speaks in a way about the patterns of authoritarianism and the way it kind of can seep in to daily life and things that seemed very distant or very foreign or, you know, not happening here are quite

00;50;24;12 - 00;50;31;08

Jonathan Hafetz

relevant. So, I mean, for the US, you know, it seems Jupiter could have a subtitle or it could happen here.

00;50;31;10 - 00;51;15;09

Isabela Amaral

I think in reality, the current democratic setbacks in Brazil and the United States are deeply connected to an authoritarian logic that corrodes institutions from within, rather than dismantling than outright. In both contexts, here and in United States, authoritarian practices operate through the erosion of trust in the electoral systems, the legitimization of independent institutions, and the mobilization of disinformation and polarization.

00;51;15;15 - 00;52;14;08

Isabela Amaral

Instead of overtly suspending constitutions as in classic authoritarian regimes, these movements hollow out democratic norms while keeping formal structures in place. This logic is authoritarian because it seeks to to weaken pluralism, silence dissent, and concentrate power, whether by pressuring courts, attacking the press, or fostering hostility against minorities. Both Brazil and the US illustrate how contemporary authoritarianism you realize less on military force and more on populist mobilization, culture wars and digital networks to destabilize democracy from the inside.

00;52;14;11 - 00;52;36;01

Isabela Amaral

In this sense, the events in both countries are not isolated, but part of transnational pattern of democratic erosion that reflects the persistence and adaptation of authoritarian practices in the 21st century, I think.

00;52;36;03 - 00;52;47;18

Jonathan Hafetz

Yeah, that's so well put. And I think it's why it shows why the film, you know, is important to understanding what happened in Brazil, but also speaks more broadly to issues around the world.

00;52;47;20 - 00;53;17;29

Isabela Amaral

I think, this question of all territories and the persistence of all territories and is important, but what strikes me most about, see here is not just the portrait of a dark era, but how state violence did not simply vanish with the regime in 1971, who Baines Paiva was taking from his home by the military and never returned.

00;53;18;01 - 00;53;55;14

Isabela Amaral

And decades later, in 2018, pending, he was killed in Brazil inside his home, allegedly by the police. Different times, different contexts, yet both lives cut short by state force. And in here we have a lot of violence, and the film reminds us that, like, it only seemed like so many murders and lives. Today, countless women in Brazil carry the burden of memory, justice and dignity.

00;53;55;16 - 00;54;34;20

Isabela Amaral

The Constitution change it. Rights are on paper and on reality, but their promise is still hasn't reached everyone equally. And this is why the film resonates so strongly today. And to me, in a country where authoritarian nostalgia reemerged under Bolsonaro and where state violence to excessively targeted youth black man in poor communities, I'm severe is not only about 70s, it's about the present.

00;54;34;26 - 00;54;53;09

Isabela Amaral

It's an alarm that democracy is fragile and the memory is essential to defend it. As long as there are people who fight, who remember, and who refuse to normalize violence. I think we are still here, you know.

00;54;53;12 - 00;55;04;23

Jonathan Hafetz

Well, Isabella, I want to thank you so much for coming on the podcast and talking about I'm still here. And for those listening, if you haven't seen this movie, you should see it as soon as you're able.

00;55;04;25 - 00;55;26;12

Isabela Amaral

So thank you, Jonathan. It was a great pleasure for me. I would like to express my sincere gratitude for the opportunity to share these reflections and to engage in such inspiring dialog about this film. Thank you very much for the attention and for the generosity of this exchange.

Further Reading

Atencio, Rebecca J., Memory’s Turn: Reckoning with Dictatorship in Brazil (2014)

Lima, Ana Gabriela Oliveira, “Corrected death certificates for Herzog, Rubens Paiva,and one hundred others are celebrated in a ceremony,” Folha de S. Paulo (Oct. 8, 2025)

Paiva, Marcelo Rubens, I’m Still Here (2025)

Pitts, Bryan, Until the Storm Passes: Politicians, Democracy, and the Demise of Brazil’s Military Dictatorship (2023)

Weinberg, Eyal, “Transitional Justice in Brazil, 1970s–2010s,” Oxford Research Encyclopedia (2022)

Isabela Amaral is a Ph.D. candidate at the State University of Rio de Janeiro (Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro – UERJ), a temporary lecturer in Constitutional Law at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro – UFRJ), and a legislative advisor at the State Legislative Assembly of Rio de Janeiro.