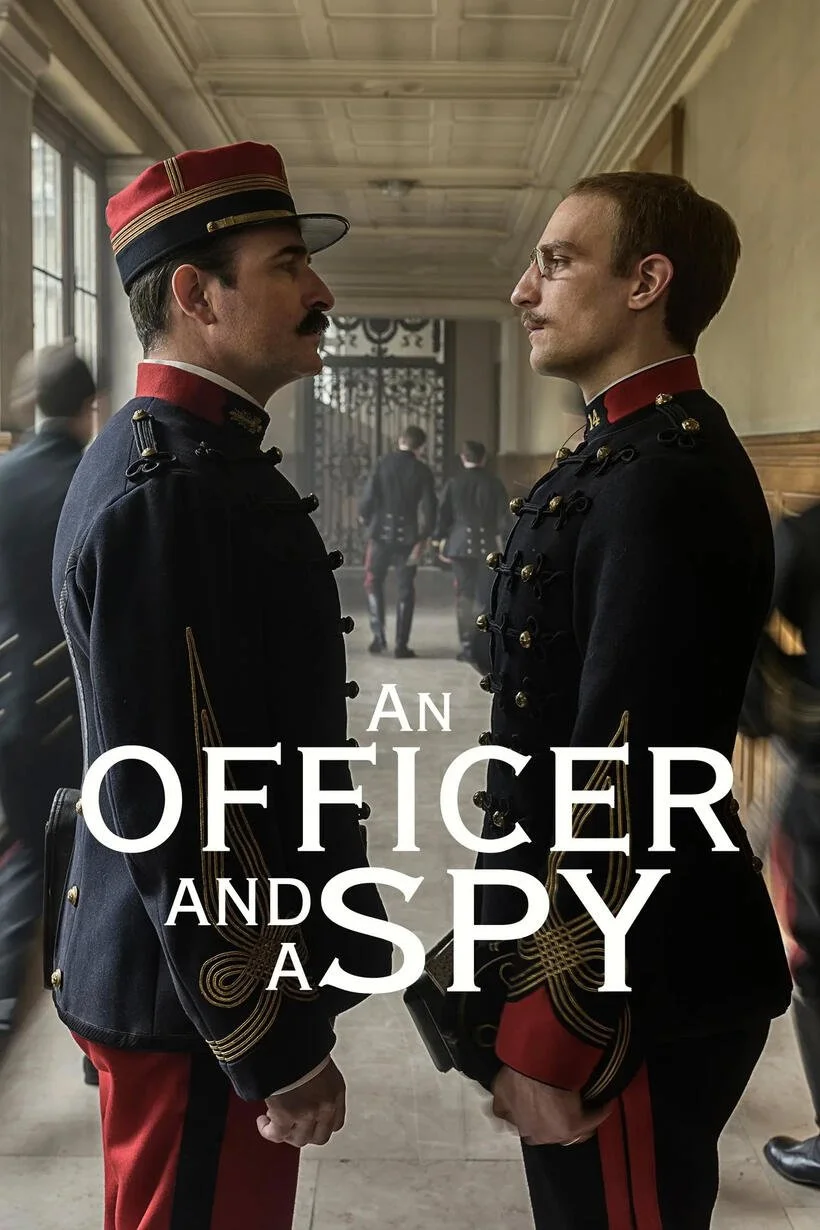

Episode 51: An Officer and a Spy (2019)

Guest: William Schabas

Listen Anywhere You Stream

~

Listen Anywhere You Stream ~

An Officer and a Spy (J’accuse in French) is director Roman Polanski’s 2019 film about the Dreyfus Affair in France. The Dreyfus Affair is one of most significant events in late 19th/early 20th century, an event whose implications reverberated for decades in France and around the world. The Dreyfus Affair centered around the military trial of Captain Alfred Dreyfus on charges of treason. Wrongly convicted based on secret evidence and false information, Dreyfus’s case would become a cause célèbres and synonymous with a miscarriage of justice. It also exposed and exacerbated tensions within French society while underscoring deep and pervasive levels of antisemitism. Based on Robert Harris's 2013 novel of the same name, An Officer and a Spy focuses on the role of George Picquart, the military officer who helps uncover the truth behind Dreyfus’s wrongful conviction, and Picquart’s complex relationship with Dreyfus himself. Hewing closely to historical fact, the film highlights critical issues around law, truth, and justice, at the heart of the Dreyfus affair and why it remains so relevant today.

25:38 How the Dreyfus affair divided French society

30:16 Other films about the Dreyfus affair

33:54 The controversy around Roman Polanski as director

38:43 Public law affecting water allocation and management

39:21 Legacies of the Dreyfus affair

45:13 The role of Colonel Henry

0:00 Introduction

3:02 An overview of the Dreyfus case and key players

5:54 Georges Picquart

13:14 The struggle to overturn Dreyfus’s conviction

17:54 Tensions over the Dreyfus affair and a lack of accountability

20:48 The “evidence” in the Dreyfus case

Timestamps

-

00;00;15;20 - 00;00;41;03

Jonathan Hafetz

Hi, I'm Jonathan Hafetz, and welcome to Law on Film, a podcast that looks at law through film and film through law. This episode we explore an officer and a spy was accused in about the Dreyfus affair in France. The Dreyfus affair is one of the most significant events in the late 19th early 20th century, an event whose implications reverberated for decades in France and around the world.

00;00;41;09 - 00;01;21;08

Jonathan Hafetz

The Dreyfus affair, centered around the military trial of Captain Alfred Dreyfus on charges of treason, wrongly convicted based on secret evidence and false information. Dreyfus's case would become a cause celeb and synonymous with the notion of a miscarriage of justice. It also exposed and exacerbated tensions within French society, while underscoring deep and pervasive levels of anti-Semitism. Based on Robert Harris's 2013 novel of the same name, An Officer and a spy focuses on the role of George Picard, the military officer who helps uncover the truth behind Dreyfus's wrongful conviction and Picard's complex relationship with Dreyfuss himself.

00;01;21;11 - 00;01;47;13

Jonathan Hafetz

Hewing closely to historical fact, the film highlights critical issues around law, truth, and justice at the heart of the Dreyfus affair and why the affair remains so relevant today. Joining me to discuss an officer in Spy is William Shamus. William Schein is a professor of international law at Middlesex University in London. He joined the Middlesex University faculty in 2011 after a distinguished career as a practicing lawyer and academic.

00;01;47;16 - 00;02;21;06

Jonathan Hafetz

Having previously been professor of Law at the University du Québec on Montreal and the University of Galway in Ireland. Professor Seamus is also Emeritus Professor at Leiden University and the University of Galway, honorary chairman of the Irish Center for Human Rights, and invited visiting scholar at the Paris School of International Affairs, Si Arts Po. Professor Seamus has appeared as counsel before international and national courts and tribunals, including the International Court of Justice, the International Criminal Court, the Grand Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights, and the Supreme Court of Canada.

00;02;21;08 - 00;02;45;02

Jonathan Hafetz

Professor Seamus was named an officer of the Order of Canada in 2006. He was elected a member of the Royal Irish Academy in 2007. He's been awarded numerous honors, including the Best Bayesian People, a medal for International Criminal Justice at the Association, Turn Out at What You Know, the Gold Medal in Social Sciences of the Royal Irish Academy, while also holding several honorary degrees.

00;02;45;04 - 00;02;49;12

Jonathan Hafetz

Professor Seamus Bell, if I may. Welcome to the podcast.

00;02;49;14 - 00;02;50;24

William Schabas

Thank you very much.

00;02;50;27 - 00;03;04;02

Jonathan Hafetz

So the movie centers around the arrest and trial of Captain Alfred Dreyfuss, played by Louise Earle, on charges of treason. What's Dreyfuss accused of and what happens at his military trial?

00;03;04;04 - 00;03;27;04

William Schabas

Well, of course, the film is all about Dreyfuss, except the Dreyfuss himself plays a very, very minor role in the film. We we hardly see him. And it's really the story of this Colonel Picard who who took over as the head of the intelligence wing of the French military after Dreyfuss had been convicted. He had been involved in the earlier stages.

00;03;27;06 - 00;03;49;24

William Schabas

And, he takes over, and then he he's suspicious about the evidence. He starts to examine it more thoroughly, and he comes to the conclusion that this was a miscarriage of justice, that it's a wrongful conviction, and then he has to fight with his superiors or really resist his superiors who want to just who say, this is rescue the cat, let sleeping dogs lie.

00;03;49;29 - 00;04;10;06

William Schabas

We're not going to go into this again. So Dreyfuss himself, of course, you know, it's a trial about someone who didn't do anything. He was innocent. He was in the French military. People often say that he was the only Jewish officer in it, but that's not the case. Apparently, there were several generals who were Jewish in the French military at that point.

00;04;10;09 - 00;04;29;19

William Schabas

But he was in the the head office, the headquarters in Paris. And there he was rather alone. And he was, of course, he got to that relatively high position. But at the same time, there were people who didn't really think much of Jews and, and were very, very nice to him. So he was a target that they singled out.

00;04;29;19 - 00;04;54;18

William Schabas

They had a spy. There was a leak. There was a lot of espionage going on. It was the Germans who were spying on them. And Dreyfus himself was then, labeled for the, you know, with responsibility. There was a secret trial. It all took place, secretly. And there was there was secret evidence that I think only came out decades later about it.

00;04;54;18 - 00;05;23;05

William Schabas

And there's still speculation about all of the, you know, there's stuff about it, I think probably we'll never really know about about what went on. But the fact is that he was convicted. And so the film then is is the story really of this Colonel Picard, who campaigns campaigns that mean he stays within the French military, although eventually he's imprisoned himself and he fights for a reversal of the of the verdict.

00;05;23;07 - 00;05;51;16

William Schabas

One of the thing is that someone who doesn't really play a role at all in the film. He's mentioned a few times, but he's not a character in I guess that's Polanski, and his choice is Dreyfus's brother. His older brother, who really leads the campaign. He is the one who, just the minute his brother is convicted, he's fighting and he just leaves no stone unturned campaigning to get the verdict reversed and separately, really.

00;05;51;16 - 00;06;25;22

William Schabas

And I think it's really very much in parallel. We have this effort within the French military by this Colonel Picard to challenge the verdict and to get a reverse. And of course, those two eventually those two streams merge the public campaign that Dreyfus's brother is really at the at the heart of. And then this challenging within the French military and the gathering of the evidence because this is the thing, Picard, because he's the head of intelligence, has access to some of the evidence that the others don't have, and so that the public campaign doesn't.

00;06;25;25 - 00;06;35;16

William Schabas

And of course, his position challenging the verdict adds a great deal of credibility to it as well, because he's he's the insider. He's on the inside.

00;06;35;18 - 00;06;52;21

Jonathan Hafetz

Yeah. It's a very, very interesting choice to center Picard and base the film around him. I mean, you know, in all the accounts he's pulled, the brother drives, his older brother does play the key role, but I think Picard or in terms of at least getting things started and maintaining the pressure, but I'm not sure if it would have made as good a drama.

00;06;52;22 - 00;07;17;16

Jonathan Hafetz

You know, part of the drama that Picard makes, I think, is you have him on the one hand, doing his duty, and then you have his views of Dreyfuss, which are, I think, somewhat more complex. And so the film opens with, it's told through a series of flashbacks interspersed with Picard's investigations. But it opens with Dreyfuss following his conviction at the military trial, being publicly degraded or cashiered.

00;07;17;16 - 00;07;36;19

Jonathan Hafetz

Right. His insignia medals are stripped, his sword is broken over his over the knee of his to grater, and he's marched around the grounds, military grounds in his ruined uniform, where he spat at and jeered cries of of Judas and Jew, even as he maintains not just his innocence, but his love of France and you can see, right?

00;07;36;19 - 00;07;58;26

Jonathan Hafetz

Picard has some complex views of Dreyfuss where, you know, he's somewhat anti-Semitic. We see in the beginning, right. There's a comment that he makes to his fellow officers as he's watching that Dreyfuss looks like, quote, a Jewish tailor crying over the gold he lost. Right. So I guess you can talk a little bit about Picard's views of Dreyfuss and how they change and what ways they change.

00;07;58;29 - 00;08;24;14

William Schabas

Yeah. He's not I mean, he's not, but, you know, people accuse people of being and by some else, and then they accuse them of being virulent that they saw might and, I wouldn't call him a virulent that like somebody, but he certainly wasn't, a friend didn't he had had Dreyfuss as a student, apparently in the military academy there, and he certainly didn't initially have any question about the guilt of Dreyfuss.

00;08;24;14 - 00;08;52;04

William Schabas

He believed, as did many people who later became campaigners. You know, I I've only seen the film and I've watched it a few times and read a lot about it. Jean-Georges, who was the great French socialist leader, parliamentarian who joined the campaign, who was called the Dreyfuss, as they call them. And George has also said at the National Assembly that he thought Dreyfuss not only do you think he was guilty, he didn't know why he didn't get the death penalty.

00;08;52;06 - 00;09;20;03

William Schabas

He said, you give the death penalty to the to the low life. The working class soldiers. But he's an officer from a privileged background, which he was. He was from a very wealthy family. And they said, and he gets life imprisonment. So, you know, I think he could probably make more of it. The idea is that, Picard was not a political campaigner, and he certainly wasn't, didn't challenge him by Semitism in that way either.

00;09;20;07 - 00;09;41;26

William Schabas

I think he probably never did. And, you know, the final thing or two at the very end of the film, of course, long after Dreyfus has been acquitted, Dreyfus has received the Legion of Honor and Picard is the minister of war. So this is 15 years later. So Picard is like the top military guy in the country.

00;09;41;26 - 00;10;05;24

William Schabas

Now. He's the minister of the army, you know, the Minister of war. And even then he's sort of cold with one another. They don't. It's not like they're it's not like Dreyfus feels. Dreyfus kind of irritated with Picard. He hasn't used his authority. Then to get his because this was an issue after after he was rehabilitated. After he was acquitted, he lost several years.

00;10;05;24 - 00;10;24;15

William Schabas

He spent five years in prison. And then there were several years before he was completely acquitted. And his career lost ten years of that. He should have been at the much higher rank at the end of his career. But of course Dreyfus remained. He went back to the Army. They were both very devoted to the French army and the Dreyfus.

00;10;24;18 - 00;10;47;01

William Schabas

Finally, you know, he serves in the French army in, in the First World War. He's at the Battle of Verdun. So, you know, and that's how he ends his career. But he should have ended his career several notches up with more stripes on his arm than he did. And Picard won't even change this for him later. So, yeah, it's a it's a strange relationship.

00;10;47;04 - 00;11;09;07

Jonathan Hafetz

I mean, it's interesting what Picard says at the at the end. I mean, I, I got the sense in that final scene that he's somewhat sympathetic to Dreyfus's claim, but is that, you know, he makes a reference to political changes and there's not as much support, maybe for the Dreyfuss Arts, and it's just too politically kind of costly.

00;11;09;07 - 00;11;24;02

Jonathan Hafetz

And Dreyfuss says you should do it because it's the right thing to do. But God says, no, I mean, I think it speaks also to the some of the lingering facts. If you look at the framing of the movie, you got to mention it opens with the scene of Dreyfuss being degraded, which I think is an interesting choice to open the film with that scene.

00;11;24;02 - 00;11;28;27

Jonathan Hafetz

And not a courtroom scenes, a powerful scene, and then closing with the scene with Picard.

00;11;28;29 - 00;11;47;17

William Schabas

You know, the opening scene is terrific. And, I should say, you know, the the film, I think it's beautifully made and with a huge attention to detail. The uniforms, this, all of this, the version of the film I got. And I guess we may talk about this at some point. It's it's been a bit, what's the word?

00;11;47;20 - 00;12;16;25

William Schabas

It's not easy to get this film. It's had its own experience with, being marginalized because of the filmmaker Roman Polanski. So the version I got is a DVD. I got the French version, J'accuse DVD in France, and it comes with a about a half hour film there about the making of the film, and you just see this incredible effort that was make it realistic so that the scene of Dreyfuss being he's been convicted and then he's being dishonored.

00;12;16;28 - 00;12;37;10

William Schabas

So he's having his medals stripped from it publicly, and all the soldiers are there. And of course, Picard is there, and they break the sword. The officer is doing this breaks the sword over his knee, and in real life they apparently have to stage that. So they had to file down the sword, because the guy was then confident that he could actually break the sword over his knee.

00;12;37;10 - 00;12;59;25

William Schabas

So they they set it up for the drama of breaking the sword. And then of course, he is, dishonored there. And then there are some anti-Semitic comments that are made from the crowd against him as well as people muttering sort of sotto voce, that's what that's what Picard is doing. And, you know, saying, well, the Jew finally is getting it and so on.

00;12;59;27 - 00;13;03;15

William Schabas

But tremendously a dramatic scene. And it was filmed on location.

00;13;03;15 - 00;13;34;07

Jonathan Hafetz

And yeah, it is in such a it is a powerful scene, I agree. I mean, it's a very accurate depiction of events and everything else. Obviously it has it's emphasized certain things in the story. As a Dreyfuss is convicted by Court Marshal, 1894. He sent to Devil's Island off the coast of French Guyana. Really very difficult conditions, you know, doesn't have can't even see the water that he's so close to, confined to a small cell and he gets ill, you know, you know, a lot of illness that he has to go through.

00;13;34;10 - 00;13;56;09

Jonathan Hafetz

He actually has no idea until he's eventually brought back to France, really what's going on in the case. And so he spends, I think, five years there. It's convictions not overturned until 1906 by the Court of Cassation. So but there's a lot that happens in between. We have Esterhazy, who was the real spy. Right. There's a sham court martial exonerating him.

00;13;56;11 - 00;14;19;11

Jonathan Hafetz

Zola, who finally comes out. We'll talk about him denouncing what's happened. He has a criminal libel trial. And then we have Dreyfus's second court martial in 1899. So just kind of what happens in this in this period where, as you said, it wasn't so clear necessarily to everyone that Dreyfus was innocent, but certainly increasingly it becomes very clear that Dreyfus is innocent.

00;14;19;11 - 00;14;22;28

Jonathan Hafetz

And yet he is he's still imprisoned.

00;14;23;00 - 00;14;45;00

William Schabas

Yes. Well, you know, it's very complicated. And we couldn't I couldn't do a three hour lecture and go through all the different facets of this, this case, you know, the trial and everything. And his sentencing happens very quickly. And he's even he's kept in the prison on the left bank in Paris, near the the famous cafes on the left bank.

00;14;45;03 - 00;15;09;24

William Schabas

And he's not allowed to communicate at all. The family are even afraid to publicize it because they've been warned that this is, you know, it's all it's like the kind of thing that we see these days in the terrorist trials and so on, where they're they're hidden away when they don't have the same rules, don't apply. And there's also a great deal of, you know, fake news out there and misinformation.

00;15;09;26 - 00;15;42;17

William Schabas

But after that, he gets sent to Devil's Island, where he really is persecuted. There. I mean, he's more than just putting away in prison for life, but they put him at one point in leg irons. And you see that very dramatically in the, in this one of the other films that's made about him, this early film that was made in 1899, the very beginning of cinema, there were these short films that there were ten of them, or nine of them that still are available, that go for a total of 10 or 11 minutes.

00;15;42;19 - 00;16;02;14

William Schabas

You can find them on everyone can find them easily on, on YouTube, and you see them being put in these miserable leg irons. So he was really very, very abusive. And then he's brought back following the campaign and they have a new trial and they don't hold it in Paris. They have it only in Brittany, in Rennes, near the ocean.

00;16;02;16 - 00;16;26;04

William Schabas

And they they uphold the verdict basically. And they sentence them to a shorter term. And then he is there's a negotiation that goes on where he agrees, basically with the verdict in order to get released. And this is something that upsets many people, including Zola, who and some of his defenders think that he's kind of sold out in doing this.

00;16;26;04 - 00;16;46;10

William Schabas

The poor man has spent five years on this island, and finally they make a deal where he can walk and get out of jail. And his supporters, you know, don't don't want to let go. And he does that. And then later, of course, he gets a full pardon and the conviction is reversed. And as I say, he's given the the Légion d'honneur.

00;16;46;10 - 00;17;11;20

William Schabas

This is the Legion of Honor, this great honor in France. And by then we're in the middle. This is 1905, 19 oh. And even then it's, you know, it's a hot issue. And when Zola, who is depending on what you read, people say, Zola died in an explosion, I think he was probably murdered. And I think that someone eventually did admit to doing it.

00;17;11;20 - 00;17;31;19

William Schabas

There was an explosion in his apartment in Paris, but someone had snuck in and fixed the oven so that it was going to explode. And, Zola then is brought into the pantheon, which is this, you know, great, honorable institution that only a handful of people get into. Of course, he's one of the greatest writers in the history of French literature.

00;17;31;21 - 00;18;10;03

William Schabas

And so he's being brought there. And when he's being brought there, Dreyfus is there. And someone takes a shot at him. I mean, he doesn't get badly injured, but, you know, he's being shot on the streets of Paris, going to honor someone who's at this moment or he's being introduced into the into the pantheon. And so, so this the saga of it goes on and on for well, until recently, only, 5 or 6 years ago, this ultra right politician, Eric Zimmer, who was campaigning, he was sort of rivaling Marine Le Pen to be a candidate for the president some years ago.

00;18;10;09 - 00;18;28;12

William Schabas

And Zamora made some statements saying, well, it's kind of murky, the whole thing. And it's not clear the evidence about Dreyfus sort of thing. This is you know, trying to have just pushed doubts about it. Of course, we're not getting that at the highest levels now. But the thing is, it's still out there.

00;18;28;14 - 00;18;46;07

Jonathan Hafetz

Yeah. It has persisted in. Yeah. You mentioned the assassination attempt on Dreyfus. This was earlier, right at and this is in the in the film, the lawyer, where the leading lawyer for the drive for Sergeant Leon Laws and Zola's libel trial, they also tried to kill him as well.

00;18;46;07 - 00;19;08;22

William Schabas

So, yes. Yeah, it was a great one of the great lawyers. And he was acting for, Dreyfus in the rehearing, the, the the second trial. And they're in Rennes and you see that they do the scene in the film where he's walking with Picard, they're walking to the courtroom, and then this guy comes up and takes a shot at the in these badly injured, and Picard goes chasing after them.

00;19;08;25 - 00;19;22;20

William Schabas

But, you know, Picard's 40 years old and the guy who took the shots, probably 22, and he just outruns them and they never catch him. As for the guy who took the shot at, Dreyfuss in Paris, he gets put on trial and he gets acquitted.

00;19;22;22 - 00;19;46;28

Jonathan Hafetz

And there's no, you know, relatedly, there. No, there's sort of, amnesties across the board for everyone. I mean, it covers certainly like Picard. Right. And I can show up. And Dreyfus says, but also the people in the military who deliberately fabricated evidence or new evidence was fabricated and effectively engineered and maintained a false conviction. So, you know, there's like that whole other dimension of the amnesties.

00;19;46;28 - 00;20;01;04

Jonathan Hafetz

Well, I think interestingly, they it wasn't granted to Dreyfuss because it was a pardon. He was able to get the still get the conviction reversed. But as everyone else, there was Zander's deal, which I think is kind of problematic. Think about it from kind of a transitional justice kind of lens.

00;20;01;06 - 00;20;18;17

William Schabas

Well, you know, they treat it. There's this whole idea that, you know, this was like a family quarrel in France, and the families fought with one another. And then they sort of it was a bad patch. And let's just move on. There's a lot of that about it. You know, the French have a very I mean, I live a lot of the time in France.

00;20;18;17 - 00;20;42;06

William Schabas

I've gotten to know them rather well. And they have a it's complicated. And the Dreyfuss wasn't the end of it, because it was only very recently in France that you could have a major exhibition at the archives about pay to learn about the occupation and about accountability for that. And as I say, you see these characters like the more running for president of France.

00;20;42;08 - 00;20;48;06

William Schabas

I mean, he didn't come close, really, but he made a lot of noise. And this is in the last five years.

00;20;48;08 - 00;21;19;12

Jonathan Hafetz

Just going back to the trial for a minute. Right. I think it's it is a long and complex history. Right. You know, we have the trial and retrial of Dreyfus and it kind of in between. Right. You have the it's a campy events basically the sort of the revealing that the famous or the key piece of evidence, the letter that Dreyfus had supposedly written that was evidence, the border row that he was selling secrets to the Germans was written by this Esterhazy military officer, who was a dad, as a scoundrel.

00;21;19;18 - 00;21;37;15

Jonathan Hafetz

Right. And it comes kind of clear. So you have that comes out and there's a you know, he's exonerated. They tried to put him up in a sham court martial. He's exonerated. And then Zola responds with his famous J'accuse! Probably like the most famous, influential op ed in history, I guess, right, to mobilize France. So. And then only then do you get the retrial.

00;21;37;15 - 00;21;59;26

Jonathan Hafetz

It ran in 1899. So I guess I'm saying it really becomes kind of a political affair. It's not so much, you know, a legal maneuverings and kind of briefs and, arguments that get the case pushed back and ultimately partially reversed or mitigated in the 1899 judgment. But it's the political battle, right. And that you had if you could talk about kind of what the political affair.

00;21;59;28 - 00;22;19;28

William Schabas

Yes, absolutely. You've referred to this central piece of evidence they called the border wall, which is, just a French word for, you know, like, like a copy of a document or a piece of. It's a scrap of paper. Really? And the French have a spy in the German embassy who's a cleaning woman. And so she collects the.

00;22;19;29 - 00;22;44;24

William Schabas

She takes out the rubbish, she collects the rubbish bins and brings them the paper. And so there they get this border wall which has been torn apart, and they have to piece it all together. And then there's this. Absolutely, you know, pseudoscientific effort to analyze the handwriting that gets one of the great French criminologists involved. He he's a dishonest, lying witness as well.

00;22;44;24 - 00;23;05;28

William Schabas

This is the the guy named Bertha. You know, in, in in French. I went to law school in French. And we talk about Bertie Honors, which is fingerprinting. He invented fingerprinting as a technique of forensic, investigation. And he wasn't an expert on the handwriting at all. But he had a look at and he said, oh, it looks like that's Dreyfus's handwriting.

00;23;05;28 - 00;23;32;11

William Schabas

And of course, it didn't. When anybody who knew knew the subject would say, no, it isn't. And then he developed a theory that he called self forgery, where this was Bertie Owen's theory that Dreyfus was actually trying to make it look like he had done it so that it would look like a forgery, all just totally contrived. But, you know, it was really, I mean, lots of people have thought about this, and they'll be doing it for for decades and centuries to come, I suppose, as well.

00;23;32;11 - 00;23;52;07

William Schabas

But, you know, my own take on it is that this was a case. It wasn't as if he was singled out for a sham trial because of anti-Semitism, but it contributed to it and the way people looked at him, and it just meant that there was a whole lot of unfairness along the way that people were prepared to look the other way on.

00;23;52;09 - 00;24;18;24

William Schabas

The French wanted to hold somebody accountable. The French military wanted to hold somebody accountable, and they got into this. And then, as you say, it gets in then to the political sphere where it is really, an issue of where where people are fighting within the families and themselves and disputing it and disagreeing. You can't have a proper dinner party because you're going to get in a fist fight about whether or not he's he's guilty.

00;24;19;00 - 00;24;53;26

William Schabas

And it's it's the sort of thing we see today still with the with trials that have the political dimension to it. And Polanski brings up some of that, of course, in the in the film we see that, we see the fake news newspapers that were full of anti-Semitism and hatred and dishonesty and then we see the the honorable part of France, people like Zola and Clemenceau who campaign and Picower, who ultimately, you know to this point that he doesn't want to rock the boat at the end to get Dreyfus the promotion that he should have.

00;24;53;29 - 00;25;12;24

William Schabas

But this is a man also. You don't want to be too unfair to him. This is a man who sacrificed everything. At one point, he went to jail for Dreyfus. He sacrifices his career. The fact that he rebounded and became the Minister of War. Fair enough. And maybe after all of that, he says, listen, we've done enough.

00;25;13;00 - 00;25;15;20

William Schabas

Let's just get on with our lives.

00;25;15;23 - 00;25;35;09

Jonathan Hafetz

Yeah, I know, I agree, and I didn't see it as critical of him. It's just in the sense of just kind of being realistic about the way the, the, the tensions that still existed. I mean, I think anti-Semitism isn't, say, the reason or the overwhelming reasons. I was selected, but it does play a significant role later on in terms of the political divisions.

00;25;35;09 - 00;26;14;20

Jonathan Hafetz

And you really do have this tension within French society, reactionary forces in French Catholicism. Edward Dumont, anti-immigrant, anti Semitic versus this idea, you know, kind of Republican France. I mean, it really becomes a battle over, I think in some way the identity of French society. And Adam Gopnik wrote in The New Yorker, the Dreyfuss affair was the first indication that a new epoch of progress and cosmopolitan optimism will be met by a countervailing wave of hatred that the form the next half century of European history seemed a pretty accurate assessment to me of what I've kind of what the stakes were and what some of the broader implications were.

00;26;14;22 - 00;26;22;18

Jonathan Hafetz

It really doesn't become. It's not really about, you know, whether Dreyfuss was innocent or guilty was very clearly innocent. Right. But it was about something much bigger.

00;26;22;20 - 00;26;45;00

William Schabas

I don't know if Adam Gopnik would write the same thing about Europe today, because in some ways it was, you know, it was kind of like what we see liberal, progressive forces in so many respects. And then on the other side, you have these demagogic populist politicians, and you have some you have a lot of you're in the United States.

00;26;45;02 - 00;27;10;08

William Schabas

You get some of that right from there, from the white House these days. But certainly it was significant, you know, that that part of it is intriguing. I was always taught I remember my father speaking to me about the Dreyfus trial and thought that this was, you know, a great stain on France and was, a sign that there was some sort of deep rooted anti-Semitism that was part of the almost part of the French character.

00;27;10;08 - 00;27;29;03

William Schabas

But of course, there's a whole other side to it. And my thinking on it was, was changed recently by a book that I read by, or there that on terror, who was, you know, a great French legal personality who passed away just a year ago. And he's going to be he's going to enter the Pantheon in Paris.

00;27;29;06 - 00;27;51;28

William Schabas

He wrote a book about his family who come from what is, I think today, Moldova, Bessarabia Jews from that part of the world who immigrated at that time, at the time of the Dreyfus case. And they went to France. And he suggests that they went to France because they thought that it wasn't that there was anti-Semitism in France.

00;27;51;28 - 00;28;16;21

William Schabas

There was at least as far as they were concerned, there was Semitism everywhere. But they wanted to go to France because they saw people like Zola, and they thought if people of that level in society are prepared to fight for some lowly Jewish officer, that this is the place where we're we'll be protected. And, I went back in preparation for this and I got out the book by that.

00;28;16;21 - 00;28;39;11

William Schabas

And there again then he quotes the father of Emmanuel Levinas, great philosopher, who was a rabbi in somewhere in Eastern Europe. I don't know where exactly who said, look at France. These leaders in French society are fighting for a Jewish officer. That's where we should go. That's where we'll be safe. So, you know, there are two ways to look at all this.

00;28;39;18 - 00;29;01;21

William Schabas

The turmoil about it as well. You know, Theodor Herzl, the founder of modern political Zionism, was himself. He attended the trial, apparently, or he was there at the original proceeding. And he took that. You know, his take away from it is you'll never be safe. We've got to have our own state. But as I say, others saw it differently.

00;29;01;21 - 00;29;19;28

William Schabas

I have the feeling that in some way that this was the choice my grandparents made. They went to the United States. They all wanted to be protect, you know, be saved from an eye. Semitism. They had to go somewhere. My grandparents said, let's go to the United States. That's where we'll be safe. And it wasn't a bad decision.

00;29;20;00 - 00;29;35;01

Jonathan Hafetz

I think it's a great point. I mean, because you could look at it as kind of, you know, glass half empty, full, but that full being, as you said, the the, you know, the way that this fight ignited so many people through so much political support in the way that people were really willing to put, you know, their lives at stake.

00;29;35;01 - 00;29;54;21

Jonathan Hafetz

Picard is, as you said, he eventually goes to prison, right, for revealing secrets, which was basically trying to reveal the truth about what happened. Zola was sentenced to a year in prison. He flees to England to maintain the fight. And then people like Clemenceau. Right. Who was the publisher of the right? One of the the papers. Right.

00;29;54;24 - 00;30;12;28

Jonathan Hafetz

Dreyfus publications becomes prime minister. So it is. I mean, it's a very kind of interesting way to think about if you compare it to what would have happened, maybe in other parts of Europe where you would have had a Dreyfuss who was sentenced, based on false information and some antisemitism contributing to it, and there would have been no public uproar.

00;30;13;01 - 00;30;16;02

William Schabas

Yeah. And so say there are different ways of looking at it.

00;30;16;04 - 00;30;38;01

Jonathan Hafetz

There have been a number of other films about the Dreyfus affair. You mentioned the pioneer of French cinema, George Melia, made a series of 11 one minute shorts. So 8 or 9 remain about the Dreyfus affair, with pivotal incidents including the attempted murder of the lawyer and Devil's Island, which was incidentally shut down. The French government shut down the show.

00;30;38;01 - 00;30;59;19

Jonathan Hafetz

So sort of like early censorship. You have the probably one of the most famous William de Italy is 1937, The Life of Emile Zola, with Paul Muni in his Oscar winning role as Zola. And there's other films Richard Oswalds Dreyfus, which was set in the last years of the Weimer Republic. Jose Ferrara's 1958 accused post traumatic commentary on McCarthyism.

00;30;59;19 - 00;31;05;04

Jonathan Hafetz

So I guess it kind of. Where does Officer Aspi fit in, do you think? And to these other films?

00;31;05;06 - 00;31;26;06

William Schabas

Well, you know, as I say, that the take of the film is not really focused on Dreyfus, and you could see how another filmmaker could come along as I'm going to the film about his brother. There's a great, a great film to be made there. It is based on a book by the British writer Robert Harris, who then did the screenplay together with Polanski.

00;31;26;08 - 00;31;47;03

William Schabas

And, you know, Harris, I think is quite candid about this, that there was a bit of fiction in, in the film he created, for example, we have a little bit of, you know, a love story going on between Picasso and the wife of, of an important, French diplomat. The wife is played by Polanski's wife in the film.

00;31;47;10 - 00;32;07;26

William Schabas

And I don't think that there's any basis that could be wrong, but I think that's all just contrived fiction. But it makes for a good story as well. You know, there's a reference that I it's been in my mind since I first saw the film many, many years ago. Z by Costa-Gavras, which is a film made in the late 60s or the early 70s.

00;32;07;26 - 00;32;30;18

William Schabas

I think about the in the early 70s, about the rise of fascism in Greece in the 1960s. And there's a scene there where there's a general who's been put on trial, and the journalist comes up to him and says, is this a sham trial like the Dreyfus case? And the general says Dreyfus was guilty. So it's it's a it's a it's a line that I remember.

00;32;30;18 - 00;32;57;24

William Schabas

You hear that I quoted it many times speaking about it, about this ongoing controversy. So yeah, there's room for more. This is an elegant film and it's as I say, I think it's beautifully made and very accurate. And we've referred already to this great scene at the opening. We have some fantastic courtroom scenes as well. You know, you don't get to have a dramatic cross-examination like in, you know, My Cousin Vinny or something.

00;32;57;26 - 00;33;25;12

William Schabas

But you see, this, the rough and tumble of the, French courtrooms, which is quite interesting. I think the, the podcast about the the Goldman case recently for Davis did that with you and, and that film which I've seen, you see this, it's a, it's a jungle. It's nothing that the courtrooms are chaotic with people standing up and shouting and everything in a way that it wouldn't be the courtrooms and I'm used to seeing, that's for sure.

00;33;25;14 - 00;33;43;01

William Schabas

Very undisciplined and and quite chaotic. So you see some great scenes about that as well. And then just these lovely scenes of France, of Paris and so on, and the costumes and the carriages and all of that. You know, the ballet doc in France.

00;33;43;03 - 00;34;03;02

Jonathan Hafetz

Does. Well, not a procedural courtroom procedural in any sense. You do get that, that sense of what the early sometimes of the French courtroom and the political atmosphere around it. I mean, in addition to the sort of different focus of this film, you also have the fact which is you have to talk about it being directed by Polanski, right?

00;34;03;02 - 00;34;25;20

Jonathan Hafetz

Which, among other things, has made the film much harder to, to get, you know, he has, without going to detail his, you know, his very lavish, controversial record. And he's still a fugitive from U.S. justice for allegedly drugging and raping a 13 year old girl. And, there is one. There's a lot of controversy around the film, including at the Venice Film Festival and as well as at the Cesar Award, a protest.

00;34;25;20 - 00;34;50;20

Jonathan Hafetz

Polanski won best director. And it's more than just a fact Polanski directed it. He also tried to, seemingly connect it to his own life in interviews that he was saying that he was familiar with the workings of the apparatus of persecution, and how that inspired him, things like that. So I yeah, I don't know how you Polanski, in fact, he directed in his background in the controversy.

00;34;50;24 - 00;34;55;14

Jonathan Hafetz

It kind of affects the film, if at all. From your perspective.

00;34;55;16 - 00;35;18;05

William Schabas

You could take a view that the film is rotten to the core of simply because of Polanski's past. That's like people who don't like listening or going to operas by Wagner because he was, you know, you just dismiss it because of something else he's done that's quite extraneous to the actual great artistic and cultural contribution. And then you have, the idea that there's a message in that.

00;35;18;05 - 00;35;37;08

William Schabas

People say that about Wagner, too. Of course. They say, well, there's the you know, the, Alberich. There's actually the anti-Semite who's conspiring or the Jew or whatever. And, you know, they they read things into it, but I don't know how much. I'm not sure you can do much of that with Wagner, but I I'm wondering how much you can do with that with Polanski as well.

00;35;37;11 - 00;35;57;28

William Schabas

I know that in the interviews he gets drawn out on this, but my own impression is that the film was not made as a way of Polanski campaigning for his innocence. My suspicion is that Polanski would have preferred that people just figure that's the past. He'd done something bad in the past, and that's over, and let him get on with it.

00;35;57;28 - 00;36;21;01

William Schabas

But the interviewers of question about it, and so he's answered, saying, well, I, I did see, you know, presenting himself as being someone who's being persecuted, like Dreyfus and that's, you know, not very tasteful, to say the least. But it's an awkward issue. You know, I, I ask people about this, you know, suppose we were to learn that Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was actually a pedophile.

00;36;21;04 - 00;36;40;19

William Schabas

I'm not saying he was, but, you know, supposing so someone found some documents that came up, would we then just say, well, that's it. We're we're never going to listen to his music again. You can't do that. And Polanski is a great he's a great artist and he's a great he's a great filmmaker. But I think there is this and that's contributed to it because of what it's about.

00;36;40;19 - 00;37;16;00

William Schabas

If he had done a film about something completely different that have nothing to do with justice and a trial and all of that, you know, wouldn't have got perhaps the same the same reaction? Yeah, it's a complex thing. If you go on Wikipedia, you don't see this in the English Wikipedia. You have to go to the French Wikipedia, and you have their pages and pages and pages of detail about all of the controversy around Polanski, around the film, around him getting the awards, you know, the main award, the Cesar that he got.

00;37;16;03 - 00;37;30;20

William Schabas

But he also won that at Venice, I think. And, you know, if you could remove the name Polanski from the film and just say, you know, how great is this film? Well deserved. I mean, terrific art. And, he's a great talent.

00;37;30;23 - 00;37;52;19

Jonathan Hafetz

And it's interesting what you say about, you know, he was sort of drawn out on this. I mean, maybe there was something I feel like it's not totally unconnected to his life at some level, but it seems different in some respects. Like take the classic example of what you're describing would be something like On the Waterfront, right where Elia Kazan made the movie to basically justify, you know, informing before the House un-American Activities Committee.

00;37;52;22 - 00;38;13;18

Jonathan Hafetz

So it was really, you know, made as a, sort of a statement for him and a kind of almost a propaganda effort in that sense. So that way it's different. And, you know, the censorship issue is always tricky. I mean, you have to be aware of the implications. I mean, other films take the Oscar winning documentary No Other Land, about the Israel offensive and actions in Gaza that still has no U.S. distributor.

00;38;13;18 - 00;38;17;28

Jonathan Hafetz

So I think the problem problems when you can't access a film and judge it.

00;38;18;01 - 00;38;38;00

William Schabas

Yes. You know, I think I mentioned this maybe earlier, but the the difficulty just in finding the film, as I say, I managed to, you know, to find a DVD of it in France, but yeah, it was canceled, that's for sure. But Polanski did say that he wanted to do the film in English, because he originally said to do the film properly.

00;38;38;05 - 00;38;56;20

William Schabas

He said, was great expense. I don't know what the budget was exactly, but he said to get the financial backing to do a great film like this, he said, has to be in English because it's too limiting. If it's in French, I mean, you can double it or have subtitles, but it's not the same thing. So I don't know the details of how that all happened.

00;38;56;20 - 00;39;21;05

William Schabas

But originally he wanted to do the film in English and didn't manage him. He of course has this great team of French actors. We haven't mentioned Jean Dujardin, who was a great French actor but known for comic roles and not for this more serious role. But he's brilliant. And then they have many of the other great older actors playing the generals and stuff who are more well known in France as well, who are in the film.

00;39;21;07 - 00;39;40;19

Jonathan Hafetz

Just to kind of wrap up with any of the legacy of the Dreyfus affair today. We've talked a little bit about it, but, you know, one of the at least one other point, it that, still resonates is the way maybe a universal point is how governments in this case, really the military for, I think, its own reasons, historical reasons.

00;39;40;19 - 00;40;04;23

Jonathan Hafetz

And France just will fight and fight to suppress the truth. Right? I mean, there's really decisions at a high level, even though they know that something was really rotten in Dreyfus's case, and he was innocent not to let it go forward, that it would kind of undermine, the military and to suppress truth. I mean, so that's to me, that's one of the main takeaways that I had from the film, which is again, really, you know, almost broader than the French context.

00;40;04;23 - 00;40;09;13

Jonathan Hafetz

I don't know what your thoughts were on that or anything else that you kind of think that really resonates today.

00;40;09;15 - 00;40;31;29

William Schabas

You know, over the years I've done a lot of work on issues relating to capital punishment, particularly in the United States. And you know, there have been many cases of wrongful convictions. So not just someone who got the death penalty when they should have got 25 years or life imprisonment or something, but wrongful convictions of people who were later proved to be innocent.

00;40;32;02 - 00;40;55;27

William Schabas

I think we're still looking. There may be only 1 or 2 cases people have identified where someone was finally executed, but these were people who were just, in some ways, I mean, not poor, impoverished defendants. That was not the case of Dreyfus, exactly, but he was marginalized because of his Jewish identification. That meant that he was also a vulnerable defendant, shall we say.

00;40;55;29 - 00;41;15;10

William Schabas

And you have a trial that is shoddy. You look at it, you take a close look at it. So in the US, we have these cases where you see that, you know, you had a an inadequate counsel wasn't paying attention. There were pieces of evidence weren't gathered. But this comes out, you know, there are a lot of wrongful convictions.

00;41;15;12 - 00;41;45;19

William Schabas

And this is a good you know, it's a it's a classic of a wrongful conviction. But ultimately in most of the wrongful conviction cases, you see this closing of the ranks of a justice system. Also with the you know, this is residue, the carrot. It's been decided. We're not going to go back on it. And a great, great reluctance to reopen something that's been decided because in some ways it casts aspersions on the whole system and on the inadequacies of it.

00;41;45;21 - 00;42;18;23

William Schabas

But of course, this was a trial. This is, you know, this was an unusual trial and conviction because it was all held, basically, and there was secrecy. There was a secret file about it that was not shown. And there were different legends about what that was as well. There's even the suggestion that it brought out some evidence of someone in the German embassy who was having a homosexual relationship with someone in the Italian embassy, and this was at a time where they didn't like to talk about these things, and they considered it.

00;42;18;23 - 00;42;39;11

William Schabas

And all of them, I think documents about that came out decades and decades after the trial. But for whatever reason, you know, it is a it's a great case about that. But the combination here of the of the justice part of it, combined with the political atmosphere, I mean, it's just a great trial and I think we'll be talking about it.

00;42;39;13 - 00;43;18;03

William Schabas

You know, I'm thinking, how many trials do we have like this? I mean, Nuremberg, Eichmann, we still, you know, we've we have lots of films about Eichmann, but we haven't made enough. There'll be more because there are facets of it that still have to be made and aspects of it, and the people who were involved. And one senses that this case as well, with the great personalities and we've mentioned some of them, is all other great writer, Clemenceau, the great politician, is also a great politician who was assassinated at the outbreak of the First World War because he's a pacifist and then Proust, who is, of course, also a great facade.

00;43;18;05 - 00;43;42;29

William Schabas

And Proust writes, you know, throughout, he brings out this tension about the people who were for Dreyfus and those who were against them. And he brings that out in the remembrance of, whatever it's called now in English last time. But it comes out in his great novels as well, and there must be more. I'm sure that people give literature courses in France about all of the books that touch directly or indirectly on it.

00;43;43;01 - 00;44;11;15

William Schabas

But of course, it's also a key to understanding French politics. Then, and to some extent now. I'm a big fan of Zola as well. I suppose you could do a podcast just on all the different films about Zola's novels, but that would take too long. But the Zola house, this beautiful house that he bought when he was not very well-off but then managed to renovate as he got wealthy from the sale of his books, which is in the northern suburbs of Paris, on the banks of the sun River.

00;44;11;18 - 00;44;33;20

William Schabas

And it was closed for many years because of financial issues. And it's reopened. And next to it, they built this museum about the Dreyfus case. I've been there to visit a couple of times. It was opened by President Macron, who would underscore the significance of it all. And there's there's more. I think there's going to be another exhibition.

00;44;33;20 - 00;44;55;01

William Schabas

I saw one once at the at the Jewish History Museum in Paris, and I think there's a new exhibition that's planned about it. There are statues. There's a famous statue of Dreyfus on the left bank, but even its location was controversial, and they wanted to have it by a military academy. And the army didn't like that. And it shows him with the broken sword.

00;44;55;04 - 00;45;10;14

William Schabas

It's great. And then they have a replica of it in the courtyard of the Jewish History Museum, which is on the on the right bank in the shadow of the Pompidou Center, which is a landmark that people will know. They don't know the Jewish History Museum as much.

00;45;10;16 - 00;45;32;24

Jonathan Hafetz

Yeah. The sort of history in the way reverberates is so interesting. And you got to mention many of the kind of luminaries around the case. They're also the kind of the scoundrels and the bad people. And that's the one that's really centered in the film. Is this Colonel a military officer, Henry, who's below ego, who was, one of the ones who helped kind of orchestrate, dreyfus's conviction.

00;45;32;24 - 00;45;49;22

Jonathan Hafetz

But then even worse was the one who sort of devised, whether under orders or not, false evidence at the retrial, which was submitted in secret. He's ultimately, you know, there's ultimately a duel fought between Cam and Picard, but he's a he's a fascinating character. Probably worth mentioning.

00;45;49;25 - 00;46;08;04

William Schabas

Yes, he is, and he plays, you know, he plays a significant role in the drama because of his relationship with Picard, because he was there. Picard. Heroism. When they appoint Picard to be the head of the. You see, this is the the, counter-espionage really is. That was the office of the French military, and Picard was appointed there.

00;46;08;06 - 00;46;26;17

William Schabas

This is well before Picard. He doesn't come in there with an agenda to to get the conviction reversed. He thinks Dreyfus is guilty. So he inherits Henry, who works for him and who is, maybe thinks that that should have been his job or something. But he's he's really his his second in command or one of his second in command.

00;46;26;25 - 00;46;50;21

William Schabas

But someone who is is more invested than Picard was in the conviction. And so he doesn't want to overturn that. And then he gets into actually forging documents himself. Once the controversy breaks, he tries to undermine it by actually forging documents himself. And that comes out. And that's where he gets he gets sent to jail. But in the meantime, they have this this duel in old there.

00;46;50;26 - 00;47;14;01

William Schabas

There were some other duels as well associated with it. But this is the one that's in the film. And there's great drama about the duel and Picard. It's a sword fight. Very well done and very exciting. And he got to Picard code to finish them off, but finally he just walks away from it and doesn't do it. But, you know, he put his life on the line about as people did in those days.

00;47;14;04 - 00;47;37;17

William Schabas

And then Henry gets exposed and he gets sent to jail and commits suicide. Well, we don't see the gory details of slitting his throat, I think, in this film, but it's in the the old film, the one that was made in 1899 by Amelia's, has that scene of, of actual suicide where you see you see a it only lasts a minute the whole episode in the film.

00;47;37;17 - 00;47;55;28

William Schabas

And you see Anne-Marie there in this cell, acting very vexed and disturbed, and then he turns his back and you see him go like this, and then, you know, these were early days in cinema. They didn't have all the experience of the art directors have now in the modern day cinema and all of the props and all of this.

00;47;56;03 - 00;48;15;22

William Schabas

And then you see blood all over. I guess it was just, you know, it was a stage, like on the stage. And then you see him lying on, on the ground. And when you had that, this sort of sealed the idea of this whole trial was a hoax and a frame up and all of that. But it's an important part of the film, and that character gets played up.

00;48;15;22 - 00;48;37;29

William Schabas

But these were decisions, I guess, between Polanski, the filmmaker and Harris, whose story it really is. He wrote this novel and, novel. It's not a novel, but it's a there's there's some fiction in it, but it's pretty accurate. And it's a great read as well, the book. But, you know, I don't want to say I'm not sure that I would be one of these people to say, well, the film was good, but the book was better.

00;48;38;01 - 00;48;41;19

William Schabas

Get the film. The film was is really worth seeing.

00;48;41;21 - 00;48;59;24

Jonathan Hafetz

It really is. And and as you said, I think the George Bailey is, you know, opening, which are fascinating from a number of perspectives. And the take on the Dreyfus affair and also just how you shot things like the suicide scene 100 plus years ago, and that's easily available. But I again, often it's by is certainly I think, well worth watching.

00;48;59;24 - 00;49;16;26

Jonathan Hafetz

And, you know, you just start peeling as you're suggesting, sort of peeling like an onion. Just peel away at the Dreyfus have been there's so many different levels and so many different overlapping themes which continue to resonate today. Well, I want to thank you so much for sharing your insights and expertise. Great to have you on as a guest.

00;49;16;28 - 00;49;20;25

William Schabas

I enjoyed doing it. Thanks for inviting me to do it. And it's a great pleasure.

Further Reading

Begley, Louis, Why the Dreyfus Affair Matters (2009)

Bredin, Jean‑Denis, The Affair: The Case of Alfred Dreyfus (1986)

Doherty, Thomas, “From Méliès to Polanski: The Dreyfus Affair on Film,” Cineaste (2020)

Harris, Robert, An Officer and a Spy (2013)

Read, Piers Paul, The Dreyfus Affair: The Scandal That Tore France in Two (2013)

Samuels, Maurice, Alfred Dreyfus: The Man at the Center of the Affair (2024)

Zola, Émile, The Dreyfus Affair: J’Accuse and Other Writings (1998)

William A. Schabas is professor of international law at Middlesex University in London. He joined the Middlesex University faculty in 2011 after a distinguished career as a practicing lawyer and academic, have previously been professor of law at the Université du Québec à Montréal and the University of Galway. Professor Schabas is also emeritus professor at Leiden University and the University of Galway, honorary chairman of the Irish Centre for Human Rights, and invited visiting scholar at the Paris School of International Affairs (Sciences Po). Professor Schabas has appeared as counsel before several international and national courts and tribunals including the International Court of Justice, the International Criminal Court, the Grand Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights and the Supreme Court of Canada. Professor Schabas was named an Officer of the Order of Canada in 2006. He was elected a member of the Royal Irish Academy in 2007. He has been awarded the Vespasian V. Pella Medal for International Criminal Justice of the Association internationale de droit pénal, the Gold Medal in the Social Sciences of the Royal Irish Academy, and he holds several honorary doctorates.