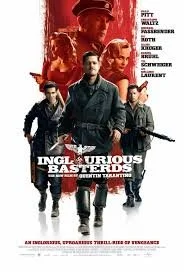

Episode 53: Inglourious Basterds (2009)

Guest: Renana Keydar

Listen Anywhere You Stream

~

Listen Anywhere You Stream ~

nglourious Basterds (2007), written and directed by Quentin Tarantino, revolves around two plots to assassinate Nazi leaders during the closing years of World War II. One plot centers on a secret band of Jewish-American soldiers under the command of Ltn. Aldo Raine (Brad Pitt)—the “Basterds”—who terrorize Nazis. The other involves Shosanna Dreyfus (Melanie Laurent), a young Jewish woman who narrowly escapes death at the hands of notorious “Jew hunter” Hans Landa (Christoph Waltz) and flees to Paris where she runs a cinema under a false identity. The plot lines converge at the Paris cinema where the Basterds and Shosanna are each separately plotting to kill Hitler and other Nazi leaders while they are attending the premiere of a German propaganda film. The film utilizes alternate history to explore themes surrounding the pursuit of justice against the perpetrators of mass atrocities and the complex relationship between law and vengeance.

27:03 The limits of legalistic responses to atrocities

32:24 The role of cinema in Nazi Germany

39:00 Narratives of progress

44:10 Ending with a primal moment of revenge

0:00 Introduction

2:37 Reimagining the arc of justice

8:00 Alternatives to the progress narrative

16:51 The power of violence and revenge

21:56 Counterfactuals and alternative histories

Timestamps

-

00;00;16;07 - 00;00;46;25

Jonathan Hafetz

Hi, I'm Jonathan Hafetz, and welcome to Law on Film, a podcast that looks at law through film and film through law. This episode we look at Inglourious Basterds from 2007. Written and directed by Quentin Tarantino, which revolves around two plots to assassinate Nazi leadership during the closing years of World War Two. One plot centers on a secret band of Jewish American soldiers under the command of Lieutenant Aldo Raine, played by Brad Pitt, the so-called bastards who terrorize Nazis.

00;00;46;27 - 00;01;14;12

Jonathan Hafetz

The other plot involves Shoshanna Dreyfus, played by Melanie Laurent, a young Jewish woman who narrowly escaped death at the hands of notorious Jew hunter Hans. Landa, quits over Walt's character and flees to Paris, where she runs a cinema under a false identity. The plot lines converge in the Paris cinema, where the Bastards and Shoshanna are each separately plotting to kill Hitler and the other Nazi leaders who were in attendance of the premiere of a German propaganda film.

00;01;14;15 - 00;01;44;10

Jonathan Hafetz

By engaging an alternate history to spin a tale of revenge, the film explores the complex themes around different ways of obtaining justice against the Nazis and those who commit mass atrocities. Joining me to talk about Inglorious Bastards is Renana Keydar. Renana is an assistant professor of law and digital humanities at the Hebrew University, where she is also academic director of the center for Digital Humanities and has the Alfred Landecker Lab for the Computational Analysis of Holocaust Testimonies.

00;01;44;16 - 00;02;07;06

Jonathan Hafetz

Professor Kaydar is the recipient of the prestigious Allen Fellowship for Outstanding Young Researchers. She holds an LLB in law and a B.A. in Political Science from Tel Aviv University, and a doctorate in Comparative Literature from Stanford University. Professor. Here I was a postdoctoral fellow in the Minerva Center for Human Rights and a research fellow in the Martin Buber Society of Fellows at the Hebrew University.

00;02;07;08 - 00;02;33;19

Jonathan Hafetz

She also previously served as a legal advocate in the Israeli State Attorney's Office. High Court of Justice Department. Among her numerous publications, Professor Godard, the author of Lessons in Humanity Reevaluating International Criminal Laws Narrative of Progress in the post 9/11 era, which uses Inglourious Basterds to explore a range of issues surrounding international criminal justice. Professor Keydar, Renana, welcome to law and film.

00;02;33;21 - 00;02;36;17

Renana Keydar

Hi. Thank you very much for having me, Jonathan.

00;02;36;20 - 00;02;43;00

Jonathan Hafetz

So what prompted you to write about Inglorious Bastards in the Journal of International Law?

00;02;43;03 - 00;03;21;10

Renana Keydar

Well, that was the end of a long journey that I took with Quentin Tarantino and his movie. When I first saw the film, what struck me as the most interesting about it is how it plays with counter history, with counterfactual history. For me, that was really what, you know, struck my initial interest in the film. And when I was writing my thesis, my dissertation on conceptions of justice in post atrocity situations, I was thinking about how that movie is a prime example of reimagining what justice could have looked like.

00;03;21;12 - 00;03;44;16

Renana Keydar

And when I was, you know, trying to formulate it, formalize it more in academic terms, I realized that the movie force inadvertently or, you know, I don't think that Quentin Tarantino went into law school thinking about death or anything, but the movie, in a way, portrays a counter narrative not only to what happened in 1944 and 1945, which is when the movie takes place.

00;03;44;16 - 00;03;52;24

Renana Keydar

You know, the plot of the film, but also to the entire arc of justice as we imagine it from the Nuremberg Tribunal onwards.

00;03;52;26 - 00;04;12;08

Jonathan Hafetz

Okay. So that arc. Right. And you refer to that, and that is referred to in the academic literature as a progress narrative. Right. And that's the narrative in modern international criminal law that often starts with the Nuremberg tribunal after World War two. Right. And continues up today. So what is the progress narrative and how does it function in international law?

00;04;12;11 - 00;04;34;13

Renana Keydar

Well, if we start from 1945, 1944, even when the discussions on how to prosecute the Nazis, after we'd already daylight forces, were imagining the end of World War Two when they saw the progress after the invasion of Normandy and everything. And they're starting to play around with the idea of what will they do with the Nazis. And, you know, how will they prosecute them?

00;04;34;13 - 00;04;56;15

Renana Keydar

How will they, in effect, achieve justice? Not so much for the Holocaust, but mostly for the crimes of aggressive war. You know, during World War Two and, you know, the very different topics that came out, the different solutions that were thought of. I won't go into the whole discussion. Much has been written about it was anything from summary executions, just, you know, put them against the wall and shoot them all.

00;04;56;17 - 00;05;21;12

Renana Keydar

Something that was, you know, thought about also by prominent officials in the Allied forces all the way to really inventing this kind of a very different notion of justice that I would call in my writing the enlightenment justice. You know, justice is enlightenment. You know, let's take them to court. Let's teach them what they did wrong. Let's teach humanity how barbarian.

00;05;21;15 - 00;05;50;27

Renana Keydar

You know, barbarous was the behavior of the Nazis and how we as society is humanity can move forward. So from the get go, the entire premise of the Nuremberg Tribunal was about educating a new generation of people of humanity about being better, doing better. And part of this was to put the Nazis in their suits, in their uniforms, in the courtroom, you know, giving them their day in the courtroom.

00;05;51;00 - 00;06;14;05

Renana Keydar

And they, you know, sure did got their day if anyone remembers him. Daring speech. Speech. I mean, it was his interrogation by the Allied forces, by the prosecutor. But if anyone remembers that or wants to look back at it, that was a complete act of performance by Girling, who was anyway, you know, revered as the, you know, very glorious bastard.

00;06;14;07 - 00;06;41;14

Renana Keydar

So we said, this is the narrative that propels the entire Nuremberg endeavor. You know, and since then onwards, entire criminal law endeavor, international criminal law endeavor is about achieving this kind of, I want to say, progress, but more giving these moments of enlightenment, of teaching humanity how to become better after events of mass atrocity.

00;06;41;17 - 00;06;55;10

Jonathan Hafetz

And so I'll play right now a clip from US chief prosecutor and U.S. Associate Justice Robert Jackson's opening statement tribunal, which quote, in the article very famous, which I think encapsulates this idea.

00;06;55;13 - 00;07;26;10

A great privilege of opening the first trial in history for crimes against the peace of the world imposes a grave responsibility. The wrongs which we seek to condemn and punish have been so calculated, so malignant and so devastating that civilization cannot tolerate being ignored.

00;07;26;12 - 00;07;59;23

Because it cannot survive there being repeated that prior great nations, flushed with victory and stung with injury, stay the hand of vengeance and voluntarily submit their captive enemies to the judgment of the law is one of the most significant attributes that power has ever paid to reason.

00;07;59;26 - 00;08;29;10

Jonathan Hafetz

And so in your article you describe, you know, this journey from Jackson's historic opening statement to the bastard's imagined to call for arms seven decades later in in the film, as a journey from a moral rhetoric that rejects acts of revenge as an official response to unimaginable crimes, to what you call state actions and their popular perception that indicate a turn away from this narrative of progress in favor of vengeful policies.

00;08;29;12 - 00;08;35;20

Jonathan Hafetz

Here's Aldo Raine's opening speech to the bastards about putting together a team.

00;08;35;23 - 00;09;03;05

My name is Lieutenant. Out go rain. And I'm putting together a special team. And I need eight soldiers. Hey, Jewish American soldiers. Now, y'all might have heard rumors about the armada happening soon. Way out. We believe a little earlier we're going to be dropped into France dressed as civilians. Once we're in enemy territory as a bushwhacking guerrilla army, we're going to be doing one thing and one thing only.

00;09;03;08 - 00;09;25;03

Killing Nazis. I don't know about y'all, but I sure as hell didn't come down from the goddamn Smoky Mountains across 5000 mile water, fight my way through half of Sicily and jump out of a fucking airplane to teach the Nazis lessons in humanity. That's. You ain't got no humanity. No, no. But soldiers of a Jew hating, mass murdering maniac.

00;09;25;03 - 00;09;51;22

And they need to be destroyed. That's why any and every sumbitch we find wearing a that's uniform, they're going to die. I'm the direct descendant of the mountain man, Jim Bridger. That means I got a little engineering, and now a battle plan will be that of an Apache resistance. We will be cruel to the Germans. And through our cruelty, they will know who we are.

00;09;51;24 - 00;10;18;29

And they will find the evidence of our cruelty. And the disemboweled, dismembered and disfigured bodies. The brothers we leave behind us. And the German won't be able to help themselves, but imagine the cruelty their brothers endured at our hands and our boot heel and the edge of our knives. And the German will be sickened by us, and the German will talk about us, and the German will fear us.

00;10;19;01 - 00;10;41;18

And when the German close their eyes at night and they're tortured by their subconscious for the evil they have done, it will be with thoughts of us that they are tortured with. Sound good? No, sir. That's what I like to hear. But I got a word of warning. For all you would be warriors. You join mock man, you take on them.

00;10;41;18 - 00;10;47;07

It a debit you owe me personally.

00;10;47;09 - 00;11;04;17

Each and every man under my command owes me 100 Nazi scalps. And I want my scalps. And all y'all will get me 100 Nazi scalps taken from the heads of 100 dead Nazis are. You will die, John.

00;11;04;19 - 00;11;10;08

Jonathan Hafetz

So how do we get from Jackson Robert Jackson to Aldo Raine?

00;11;10;11 - 00;11;50;17

Renana Keydar

Yeah. So from stay behind of vengeance to let's kill them all. Yes. That I mean, I think for me that that was the question with which I started this, you know, in a way, this inquiry, what happened, what happened to us. And I think the answer is both historical and psychological. Not at the time. I mean, psychology, but, you know, in the psychology of narratives, let's say, and on one level, we see that the entire effort of the Americans, of Justice Jackson as the chief prosecutor, the American prosecutor, is to banish away any not even sentiment of revenge, but even the implication of revenge.

00;11;50;19 - 00;12;16;01

Renana Keydar

Justice Jackson or Prosecutor Jackson is doing everything he can to rid the trials of any such emotions and sentiments of revenge. So the concept of enlightenment is not only in the level of the type of justice we want to achieve, but also in the procedural way of achieving it. It meant not bringing in the Jewish voice, not bringing in oral testimonies in general.

00;12;16;08 - 00;12;43;05

Renana Keydar

In the entire Nuremberg Tribunal, there were just as much oral testimonies as in the Eichmann tribe 2015 years later, which was a much, you know, a smaller trial of one, you know, culprit is against two, you know, the 22 perpetrators. 2422 it depends how you count them at the number tribunal. So we see here that Chief Prosecutor Jackson is doing everything he can to keep the tribe very, very rational.

00;12;43;07 - 00;13;25;22

Renana Keydar

So stay the hand of vengeance is not just in the type of punishment that we will meet on our perpetrators. It's also, by the way, that we will achieve this kind of justice. And for me, that was one layer of not acknowledging even very human reason in wish or will to revenge against those that really committed unprecedented crimes and completely pushing this away from the legal stage, but also from the rhetorical international arena, was a very acute act, a very premeditated act of banishment, that I wanted to draw attention to the price of Ted.

00;13;25;24 - 00;13;56;27

Renana Keydar

So that's if you want, on the more psychological narrative level, on the more practical historical level, if you want what we see when we look at all the rain in his speech, of course, it's situated in 1944, 1945, but it's in a way, a kind of a counter history or alternative history to what actually happened, gives us a different track of history that you cannot disassociate from the moment in which the film actually is produced and being filmed, which is post 911.

00;13;56;29 - 00;14;21;04

Renana Keydar

So you have here this historical moment in which we ask, did we actually manage to read our selves of revenge? So, you know, did major enterprise of international criminal law, of saying we are better than the barbarians, we do things differently. We don't shoot them against the wall. We, you know, take them to court, give them nice outfits and give them, you know, their day of justice.

00;14;21;07 - 00;14;40;20

Renana Keydar

Do we actually do that? And when the film, you know, is being produced and being broadcast, we're still hunting for some of another. And then, you know, a few years later, we also we, you know, the US Army's catch him and they don't bring it to justice. We all know what happened to Summerbee. London, the oh, we know what they tell us.

00;14;40;20 - 00;14;50;25

Renana Keydar

The theft of lives can be nothing. So I think it was a very interesting moment in which to ask did we succeed in the narrative of, you know, enlightenment and progress?

00;14;50;27 - 00;15;07;04

Jonathan Hafetz

Yeah. It's so interesting because you look at, as you say, situate you if you go back to when it was made, 2007, right. Height of global war on terror, you have targeted killing. You have Guantanamo, you have torture, right? You know, at the same time, you also have the rise and development of maturation of international criminal justice institutions.

00;15;07;08 - 00;15;18;10

Jonathan Hafetz

By this time, you have a permanent international criminal court, which is sort of, you know, in some ways the ultimate fulfillment of of the Nuremberg ideal, flawed as it may be. And so it's interesting you kind of have both of these things operating kind of at the same time.

00;15;18;13 - 00;15;40;06

Renana Keydar

Yeah. And in a way, if you want I mean, that's the power. If we take for a second, you know, the more literary perspective, that's the power of alternative histories. They show us the path not taken. Right. The show us if you want the shadow sentiments that lie under the, you know, official history. It's the alter ego of what we, you know of our human kind psyche.

00;15;40;06 - 00;16;12;14

Renana Keydar

The collective psyche. So we tell ourselves that we are not barbarians, but we go to court, that we are into progress and, you know, enlightenment, that the form of justice, we as humanity. And I'm well aware that I'm using this royal way. But the, you know, imagined collective humanity, the Americans in a way, have after 1945 when they imagined this, you know, New World order and we you know, I ask ourselves, are we so much better in what Quentin Tarantino's movies doing?

00;16;12;17 - 00;16;41;14

Renana Keydar

In my mind, you know, with this alternative history is to tell us, you know, you try to get rid of revenge, but it always lingers in the shadows. And even more than that, it gets to be much, you know, front and center when you just let it enter the door. So is both showing us what we didn't choose back then, but also how we can't really run away from it when we actually, you know, confront our, demons.

00;16;41;17 - 00;17;12;01

Jonathan Hafetz

In the movie. They're sort of, I think two scenes which you identify in your article in particular, highlight this sort of theme of revenge. So the first one, the smaller scale, is the brutal execution of this German officer, Sergeant Werner Rockman, by one of the bastards, Sergeant Donny Dinowitz, played by Eli Roth, referred to as the, quote, bare Jew who's ordered I, Aldo Raine, to effectively bash in this German officer skull with a baseball bat after the officer refuses to disclose basically what's actionable intelligence about the location of German troops in the vicinity.

00;17;12;07 - 00;17;18;28

Jonathan Hafetz

So then all the rain kind of sets the stage for this. So what's significant about this scene that you write about?

00;17;19;00 - 00;17;41;25

Renana Keydar

But it's not that you say sets the stage because it's actually the performative act. The curtains, they're right. They're all sitting around. And there is the the immediate reference to the, you know, the fun, enjoy of going to the cinema, both within the text and of course, you know, in the wink for the audience, us that sit and watch Quentin Tarantino's bloody gory plot.

00;17;41;28 - 00;18;05;03

Renana Keydar

I think what's interesting here is the, apologetic use of violence, sheer violence, the joy of violence. And of course, when you couple it with the fact that this is the bare Jew and it's worth noting all the rain is not a Jew. It's not about Jewish revenge is a South runner. He's, you know, leading this group of Americans, but some of them are Jews.

00;18;05;06 - 00;18;27;20

Renana Keydar

And the Jew Eli Roth. And the role that Eli Roth plays, is, of course, symbolizing Jewishness, American Jewishness of course, you don't have to go far to think about the Jewish American with the baseball bat and everything. You know, all these, insinuations and implications and you just see here just sheer violence for the sake of enjoying violence.

00;18;27;23 - 00;19;00;27

Renana Keydar

And that's something that we weren't allowed to enjoy or talk about politically and, you know, culturally. And of course, that's the stuff that, you know, the kind of violence that Quentin Tarantino always plays with in his movies. But here situating it within the counter, the alternative reality of World War Two, it really, you know, shed some light on, on, on the things that we do, but we do not agree to tell about.

00;19;01;00 - 00;19;29;03

Renana Keydar

Again, when you take a post 911, we already see how these are the things that we do then. And we do them and we tell them, you know, Israel has a long history of, you know, thinking about its policy with tortures. There was a big court decision about that, you know, banning the use of torture and everybody knows that still nonetheless, these investigation techniques in certain circumstances do go on.

00;19;29;08 - 00;19;54;19

Renana Keydar

So everything is always like a spoken and unspoken. And I think that it's it was very much the same in post 911 US, you know, with the controlling and everything and interrogation techniques and all these key, you know, buzzwords that came to control our, you know, way, our discourse. And what I was doing is just putting it out there telling us we enjoy violence, we deserve violence.

00;19;54;19 - 00;20;07;27

Renana Keydar

That is our pleasure, violence. And it's the Jewish soldiers that will meet this violence. And for me, it's a very powerful, you know, confrontation with our, you know, inner desires.

00;20;08;00 - 00;20;29;17

Jonathan Hafetz

And the other scene that you highlight, this is the effectively the film's climax. Interesting also occurs in the cinema. Right. So the reference to film this depicts the killing of Hitler and the other Nazi leaders, as well as a large civilian crowd in the Paris cinema, to Shoshana and her assistant. And it was also her lover, as well as several bastards also die there.

00;20;29;21 - 00;20;40;00

Jonathan Hafetz

So here's the clip of when Shoshana is image suddenly appears on the screen that had been showing the German propaganda film, just before she sets the cinema on fire.

00;20;40;03 - 00;20;47;19

For the last six three Germany, funded research from Germany.

00;20;47;22 - 00;20;48;23

After all of.

00;20;48;24 - 00;20;56;15

The current time. I know what you got, and I want you to look deep into the face.

00;20;56;17 - 00;21;14;23

Of the Jew. I'm just going to basically cut your losses. That's going to, your friend.

00;21;14;26 - 00;21;23;11

00;21;23;14 - 00;21;28;20

Some of these, you see the face.

00;21;28;23 - 00;21;34;27

To.

00;21;34;29 - 00;21;40;09

Jonathan Hafetz

So what messages and themes do you draw from this very violent and very memorable scene?

00;21;40;12 - 00;22;07;12

Renana Keydar

Well, that's a really, really powerful scene in which you see really basically Hitler being gunned down and being like, in a way, like a piece of Swiss cheese all hold up and, you know, very close up to his face and Shoshanna stays. You can do a lot. I mean, that's really the generosity of, of, you know, putting so much into these rather basic violent symbols and you can really take it to several directions.

00;22;07;12 - 00;22;31;10

Renana Keydar

What I took from, again, relates to this kind of a counterfactual history. Hitler was never cooked right. He committed suicide. Now you can play with your conspiratorial imaginations. He did. I didn't not die. Maybe he continued to live in the jungles of South America. We don't know. But you know, as much as we know as the common knowledge he killed himself and we didn't get.

00;22;31;18 - 00;22;55;05

Renana Keydar

And I'm saying it, of course, now, very provocatively, we didn't get the joy of killing him or executing him. And in a way, the movie wants us both to acknowledge that we would all like to kill him and really give us the satisfaction of really tapping into our very, very basic emotions of we want the bust. This bastard did.

00;22;55;08 - 00;23;26;26

Renana Keydar

And that's a very powerful, emotion to reckon with that. What we want is to kill our enemies. Now, to put them in a courtroom, not to send them to fancy jails, but to really just massacre them. And when we are seeing this movie, when Osama bin laden has not been caught and killed yet, but, you know, there is already the poster of the dead or alive that, you know, George W Bush is, you know, as the president is like, you know, publicizing this kind of a wanted poster.

00;23;27;02 - 00;23;51;03

Renana Keydar

We already see the transgression or, you know, reversal from this narrative of 1944, 1945. We're not going to shoot them, no summary executions. We are going to take them to court. And we see in real life, as the movie plays in the cinema, also the political agenda, the political atmosphere changing around what do we want to do to our enemies.

00;23;51;09 - 00;24;15;28

Renana Keydar

So we in a way, it's a counterfactual, but also a very strong representation of reality at the same time. And for me, that was the you know, what you said and you enjoy this, you know, this chilling, very violent, animalistic killing of Hitler while knowing that we didn't get to do that. But maybe we will get to do it with another kind of a Hitler.

00;24;15;29 - 00;24;43;02

Renana Keydar

In a way, yes, of course I'm not comparing and everything is different. But, you know, indeed, several years later, we did somehow manage to get the kick out of, you know, killing an arch enemy. It's also maybe Jonathan worth reminding that this is all a replay of what happened in a way, in the Nuremberg tribunal, where, again, if you go back to getting the cheat, he does, of course, was not indicted or provided the Nuremberg tribunal was already dead.

00;24;43;04 - 00;25;14;13

Renana Keydar

But he is the most prominent criminal, not criminal, on stage. And again, after humiliating, in a way, in his investigation, the chief prosecutor. The final, final blow of humiliation is that he commits suicide on the evening of his planned execution. So the court gives him the death verdict sentence and is supposed to be executed. And the night before, he killed himself with the cops, that he somehow finds its way to his jail cell.

00;25;14;16 - 00;25;27;25

Renana Keydar

So again, the sense of humiliation is because we didn't get the chance to kill our enemy, whether by legal means, you know, the death sentence or by just, you know.

00;25;27;28 - 00;25;51;17

Jonathan Hafetz

Plain violence to go back. I'm thinking of that moment when, after bin Laden's killed by the US, Obama appears on television in kind of very somber, very, serious, very been fact. And it's interesting because you can argue this is right, the revenge killing, but it's stripped of all the joy or the celebration, if you will. Right. That Tarantino explores, in his movie.

00;25;51;17 - 00;26;10;00

Jonathan Hafetz

And, you know, I'm not saying it's, hypercritical, but to some extent it might be sort of the hypocrisy is the tribute that vice plays to virtue, right? There's no celebration. We got him. It's just very matter of fact. So even when you have this maybe operation of this revenge, it's sort of sanitized at some respect.

00;26;10;02 - 00;26;33;25

Renana Keydar

Of course. And I think that's the tension that we always face. You know, that's what in a way, getting told us, told the Americans or the allied forces when he was on trial. History is written by the victors in a way. So the victors in this case were the Americans or the Navy Seals or whatever you want to put as the winners here, that in a way assassinated or killed during action and Osama bin laden.

00;26;33;28 - 00;26;54;21

Renana Keydar

But we are better, you know, we don't celebrate the death of our enemies. But in a way, that's what happened that day, right? We all in a way, we're happy that this guy that was in charge of, you know, really the biggest, I don't know, catastrophe on American U.S. soil, you know, that you you got what you deserve, right?

00;26;54;23 - 00;27;18;19

Renana Keydar

For me, what's strong about Tarantino is that it keep forces us through the movie faith. These primal emotions that we have now, I want to make it very clear. I do not argue that revenge needs to be part of our arsenal of legal tools. We invented a long time ago. Humanity invented the courtrooms in order to avoid an eye for an eye.

00;27;18;21 - 00;27;42;20

Renana Keydar

It's okay that the legal system works this way. I am against the death penalty, and it's not part of this conversation. But that's my private position. And I can argue against white, you know, immoral and illegal and all that. But that doesn't preclude the fact that we need to acknowledge that we are missing revenge sometimes as humanity again.

00;27;42;22 - 00;28;10;23

Renana Keydar

And I think that the split that took place in 1945, where the legal system takes care of all emotions post atrocity, is being dismantled very, you know, smartly and cunningly by Tarantino in this movie, making us very well aware of what makes us happy about the fall of our enemies. And, you know, in the right moment in time, where we were actually also doing things that are along these lines of revenge.

00;28;10;26 - 00;28;27;26

Jonathan Hafetz

Yeah. So to be, as you say, in your, I guess, aware of what you call this blind spot, not to embrace it, but to be aware of that, you know, we're talking about alternative endings in which you mention Tarantino uses in other films. He comes back to alternative endings again in 2012, in Django Unchained, deal with race and slavery.

00;28;28;01 - 00;28;46;10

Jonathan Hafetz

And then in 2019, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood The Sharon Tate Murders by the Manson Family. And so these types of alternative histories, they're adjacent or in tension with the progress narrative. But ultimately, the vision of justice at some level is something that everyone is rooting for. It's just maybe the method, right? How you get there is different.

00;28;46;12 - 00;29;13;03

Jonathan Hafetz

But there are also alternative histories about this era, the World War Two era, which have a very different ending. I'm thinking of Philip Roth's novel The Plot Against America, a later basis for the 2020 HBO mini series, which depicts the political rise of Charles Lindbergh and the takeover of America by fascists. So when talking about, like, the role of those type of alternative histories which, you know, are relevant to think about as well, of course.

00;29;13;03 - 00;29;37;23

Renana Keydar

So, I mean, it's kind of again, the Jewish philosopher thinker has a beautiful saying about the terms of history that it only goes to show that the only idea of the main idea of alternative history is to show off the indeterminate. So history that what happened did not contingently had to happen. And I find it very beautiful, because I think that's the strength of any counter-narrative.

00;29;37;25 - 00;30;00;08

Renana Keydar

It goes to remind us that history is not predetermined. History is something that is being made by human decisions, and human decisions can always take a different, you know, path. So when we chose to put the Nazis and try, it was a trap. You know, it was a choice by the Americans that were, you know, had their the upper hand at the end of World War Two.

00;30;00;08 - 00;30;24;28

Renana Keydar

It could have happened otherwise. Maybe if the Soviets were stronger, then there would be just summary executions and that's it. I don't know, that's the power of playing with counter narratives. And in a way, Philip Roth and of course, also The Man in High Castle and other narratives that imagine the defeat of America or the different track of the Comerica would have taken in 1945 or during World War two.

00;30;25;00 - 00;30;52;23

Renana Keydar

The power of that is to remind us, maybe, of the dangers that still lurk if we don't pay enough attention, if we don't pay enough attention to our blind, to our emotions, to our suppressions, if we believe that we are more enlightened than we are actually, because when we were saying before, this counter narrative is supposed to show us our blind spots, I want to add something to this.

00;30;52;23 - 00;31;13;09

Renana Keydar

It's not just to show us our blind spots, it's also to let us understand a bit better the price that we paid for our decisions, for the decisions that were made. The decision to put the Nazis in the courtroom had many good implications. It was, as you said, you know, heralded the international criminal order in international criminal law.

00;31;13;10 - 00;31;58;19

Renana Keydar

That's great. But it also had some other implications that we don't often take into account. For example, that revenge will explode at some point, for example, post 911. So when we look at something like The Plot Against America, Philip Roth plot against America, I don't see it as disconnected from the imagined reality of Quentin Tarantino. I see them as very much connected in the sense that they both, in a way, try to shed light on what we suppressed, on the things that we didn't want to admit that we might be like them in a way, whether it's more violent than we think, we are more primitive.

00;31;58;21 - 00;32;18;01

Renana Keydar

If you want to barbaric than we think we are, maybe it's more fascist than we think we are. So that's I think that's the power of these alternatives in a way that they let us know that history is only what we make of it is humans. And so we have to work very hard every day to make the right choices.

00;32;18;03 - 00;32;22;23

Renana Keydar

That's the ethics of death right there, too. Every day we need to make the right choices.

00;32;22;25 - 00;32;57;17

Jonathan Hafetz

As this is Tarantino, right? This is also, about film itself, Inglourious Basterds. We talked a little bit about like, the climax with Shoshanna Dreyfus cutting in, you know, her image cutting in to the cinema before she lights it on fire. And then we also see there's another scene in the film towards the Middle, where this British officer, Archie Hitchcock's Michael Fassbender, brilliant The Movie, who's also an expert on German film, being briefed by, General Edward Fine, actually, by Mike Myers on, Operation Kino, which is the plot to kill Hitler and other top German leaders at the cinema.

00;32;57;19 - 00;33;09;22

Jonathan Hafetz

And so this then leads into his discussion of film and the use of film by Nazi chief propagandist Joseph Goebbels, but by Sylvester Grass. So here's a discussion about film in Nazi Germany.

00;33;09;24 - 00;33;47;28

Are you familiar with German cinema under this? Yes, obviously. I haven't seen any of the films made in the last three years, but I'm familiar with it. Explained to me. Answer this last couple of hours requires a knowledge of the German film industry under the Third Reich. Explained to me over under Goebbels. Goebbels considers the films he's making to be the beginning of a new era in German cinema, an alternative to what he considers the Jewish German intellectual cinema, the 20s and the Jewish control dogma of Hollywood.

00;33;48;01 - 00;34;16;25

How is he doing five places at once? Again, you say he wants to take on the Jews at their own game. Well, compared to, say, Louis B, Mel, how are you doing? Quite well, actually. Since Goebbels has taken over, film attendance has steadily risen in Germany over the last eight years. But Louis B Maher wouldn't be Goebbels proper opposite number.

00;34;16;27 - 00;34;28;18

I believe that he's himself closer to David O. Selznick with him. Lieutenant Hitchcock's at this point in time, I'd like to brief you on operations in Iraq.

00;34;28;20 - 00;34;41;03

Jonathan Hafetz

So what role did film and, film propaganda play in Nazi Germany? And what, if anything, was Tarantino suggesting about film through the reference? In this case, just the major Hollywood studio heads?

00;34;41;06 - 00;35;06;10

Renana Keydar

Oh, okay. That's a highly explosive. But let's start with the, you know, the role of cinema for the Nazis. I mean, that's really a huge topic and much has been written about is from Leni Riefenstahl's contributions to it, many others, many propaganda movies were made. And when I said propaganda movies, you know, you have those that are labeled as propaganda movies and are what we call the reserved movies today.

00;35;06;10 - 00;35;43;03

Renana Keydar

So you're not allowed to show them in classes or in any public, viewings unless you get a special permission from a special office, as the, you know, the German bureaucracy, like, but then you have many other movies from that period that serve the same propaganda of anti-Semitism or, you know, the grandeur of Nazi regime that are not directly propaganda, but they still portray the same tropes of, you know, the Jewish coming this and, you know, all this tropes that we know about German cinema of that era, and they are still being shown.

00;35;43;05 - 00;36;18;00

Renana Keydar

So some of them, of course, and I think it tells us something both about the power of movies that were used both by fascist and by other, you know, fractions to really set the spirit and the agenda of the people, to make them prepared or to, yes, train them in the way that the regime wants. And of course, we can think about what maybe I don't want to hurt, but maybe what replaces the role of cinema in today's public discourse is that, you know, as the propaganda.

00;36;18;02 - 00;36;41;10

Renana Keydar

But that's really, in a way, a very strong illusion to, you know, to the power of cinema at the hand of the Nazis at least, or of dictators in general. Tarantino loves to play with cinema that he's, you know, that's his entire career. He's just a lover of cinema, and everything he does is in the quality with movies that really.

00;36;41;10 - 00;37;08;19

Renana Keydar

I mean, if you read his, latest writings on the, you know, the cinema, it's really a love song to cinema and all its references and things that really only he knows. He doesn't care. That's his major, mission. Why does he allude to, you know, what does it say about Hollywood heads? And how much did you know about the Holocaust and how much do they collaborate?

00;37;08;19 - 00;37;21;00

Renana Keydar

Well, that's a huge question. Yeah, it's a huge question that should be investigated. More have been investigated. It should be investigated. But the complacency is always, you know, the most difficult question.

00;37;21;02 - 00;37;39;14

Jonathan Hafetz

Yeah. I mean, it's also I think Tarantino when he says, you know, he thinks it is more, you know, Selznick or be mad, right. The Fassbinder characters, that's he's more David or Selznick, right? I mean, it's yeah, a lot of I think it's just, you know, just going down rabbit holes. But I think the larger point you make about film and the power of film, what happens through film in the movie?

00;37;39;16 - 00;38;03;04

Renana Keydar

Yeah, it's a film inside the film. Inside a film. So they watch one film, the pride of the nation. And and, you know, in this film there is another. So intercut into that is Shoshana Space, which is a film in and of itself. There's so many references here. I mean, you just sit and enjoy the Tarantino show in a way, and you, you know, accept it on its own terms.

00;38;03;06 - 00;38;24;09

Jonathan Hafetz

So the film is fictional, but there was a secret British unit known as the X troop organized by Churchill, who I was in favor of more vengeance after World War Two and not the trial. Right. But anyway, which consisted of Jewish refugees from Germany and Eastern Europe who collected information about and fought on the front lines against the Nazis.

00;38;24;15 - 00;38;27;27

Jonathan Hafetz

So any thoughts about this group as we're talking about the film?

00;38;27;29 - 00;38;59;13

Renana Keydar

So, you know, it's not there were several of these kind of organizations. There was also an organization called Netcom, which is literally revenge or Tor revenge to avenge. That was led by a ABBA Kovner, who was one of the parties and leaders Partizan heads and later became also gave testimony in the upcoming trial. A very lengthy testimony. A lot of it was propaganda for the Partizan groups and they also tried their way revenging the Holocaust.

00;38;59;15 - 00;39;26;23

Renana Keydar

What is very important to say is that there wasn't much place or desire for vengeance by the government. One of the things that became very clear when I heard many support and brought to Israel from Argentina in this very famous Mossad operation, 15 years after the Nuremberg tribunal, is the pride that the Israeli society has in not being vengeful.

00;39;26;25 - 00;39;55;04

Renana Keydar

And that's really an interesting question, you know, because unlike maybe the Jewish Americans or the Americans in general, Israel is the nation of the survivors. They are the ones who lost everything to the Nazis. And what you see in 1960, in 1961, in the public discourse around, the ultimate prize is a very strong sentiment that correlates of corresponds to this Nazi progress.

00;39;55;07 - 00;40;19;11

Renana Keydar

But we are better. So we are going to put it I'm gonna try we're going to do it in a court of law by the law, we had a very fair procedure, a fair way. And that's going to be our revenge. I mean, that's what's been going on. David, the Israeli prime minister, that's what he says. Our revenge is the establishment of the State of Israel, an expert system that will put Eichmann on trial.

00;40;19;13 - 00;40;51;18

Renana Keydar

And for me, that's an interesting, because we're not talking about something that happened 70 years after the Holocaust. That's 15 years after the Holocaust. Survivors are, you know, killing Israel. And still you managed to get this very wrong and stubborn narrative of progress in a way that shows you that maybe the strength or the success of the Nuremberg tribunal, you know, so you can really light up your imagination with groups like, you know, the X group or Do Not Come Group.

00;40;51;21 - 00;41;11;10

Renana Keydar

But at the end they were very, very minor, almost eccentric examples that did not succeed. By the way, also, what you do get is the dominance of the narrative progress that really took hold even within the young, you know, the nascent Israeli country, Israel state.

00;41;11;12 - 00;41;30;23

Jonathan Hafetz

And you see also that progress. Like it's just goes a little bit off topic, but how a lot of the energy for subsequent tribunal starts to fade. You get a lot of the Nazis come back into power Nazis. Right? Not the top leadership, but others. This happens in Japan with the Tokyo tribunal as well. It doesn't have that much staying power.

00;41;30;23 - 00;41;39;28

Jonathan Hafetz

I mean, if you look at a movie like Judgment at Nuremberg where they talk about this, and by the, you know, you really see the, the, the compromises that start being made as, as time goes on.

00;41;40;00 - 00;42;02;17

Renana Keydar

I mean, of course, politics enter into play and you have the Cold War starting. So there are bigger moves to take into account. It's not just the around narratives of justice. I wish it was in the it would have made my dissertation very powerful. Maybe. But we do see, while the Cold War takes over and we don't see anymore these endeavors of justice.

00;42;02;17 - 00;42;25;15

Renana Keydar

By the way, it's not completely straight, because the Eichmann trial does take place during this kind of period of the Cold War, and it does offer this kind of a moment of narrative of justice and progress, but it doesn't count so much within the longer arc of international criminal law for other reasons. I can go into that, but I think that deserves a different focus already.

00;42;25;17 - 00;43;08;29

Renana Keydar

But you do see, this is kind of a moment. But again, you see how international criminal law ties back or steps back into the narrative of progress the moment it can. So 1919 with the the end of the Cold War and the fall of the Soviet Empire, you see the rise of, again, this, you know, picking up where they left off in 1945 of the Anarchy of Justice, the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda and for Yugoslavia that are really facing and confronting horrendous crimes, genocide and mass killings and ethnic cleansing and the strength of the choices that were made in 1945.

00;43;09;02 - 00;43;34;21

Renana Keydar

You see how strongly they hold, because there is no New York discussion in 1990 when they built this court. It's already based on the discussions that were made in 1945. No one is now asking, should we or shouldn't we put them on trial or summarily execute them? No. That discussion was already made. So it's true that the Cold War put a damper on everything, you know, several decades long, bloody decades.

00;43;34;23 - 00;44;04;21

Renana Keydar

But when the time is right, the narrative of progress just await there to be picked up and immediately takes hold, takes prominence. So it's a very interesting arc to look at. You know, history is not written in decades. It's written in century. And you see here that after half a century of really thinking into the blood and gore of the Cold War, there is a room for the rise again of this narrative of justice, of enlightened justice.

00;44;04;23 - 00;44;10;03

Jonathan Hafetz

Any final thoughts on the on the film Inglorious Bastards?

00;44;10;05 - 00;44;44;01

Renana Keydar

Well, I have to say that one of the things I love the most is really the ultimate scene where they carved the swastika on the head of the main perpetrator, you know, then Nazi hunter, their Nazi perpetrator, and in a way that the epitomizing revenge, you know, that goes back to the most biblical moment, you know, making him the, you know, the sign of Cain and telling him, no matter what happens on the global stage, on the political stage, you may get amnesty.

00;44;44;07 - 00;45;09;11

Renana Keydar

You may be, you know, as you just said, you may even be, you know, get your American citizenship and be acknowledged as a fine citizen and everything. We don't care about this. We will inflict this kind sign on you. So no one will be mistaken. And for me, that's a very lucid moment of private, primal revenge. No politics can take away, you know, from the bastards.

00;45;09;13 - 00;45;32;07

Renana Keydar

And there's something in it that you know, really. Yet you carve it with a knife and you twist the knife to tell politics and history doesn't matter what you do. This man at least, is marked. We won't be mistaken within. And for me, it's a very nice moment for really showing us the all the levels of vengeance that we can, you know, explore and enjoy in a way.

00;45;32;09 - 00;45;53;10

Jonathan Hafetz

Yeah. I'm so glad you mentioned that scene. I mean, it is such a memorable, like a kind of coda to the film, right? When you're in Christopher Waltz. Right? It was so key to the movie, I think Hans Landa. Right. He's at the opening when they go into the farmhouse where she and her family are hiding. He's the one that, like, ruthlessly, you know, ferret out that the person who owns the house has, you know, the Jewish family in the basement has them all shot.

00;45;53;10 - 00;46;14;29

Jonathan Hafetz

She manages to get away, but at the end, right, he cuts himself. This deal knows he knows what's happening. And so he's going to, like, escape, essentially. Right. But you're it's exactly right how the rain says, you know, you're not going to get away with this. And it is it's personal. Yeah. You know, he says, Christopher Wall says, you know, you're not allowed to do this and all the rain says Matt, maybe I'll get chewed out a little bit, but that's going to really happen to me.

00;46;14;29 - 00;46;28;28

Jonathan Hafetz

I've been chewed out before, and it it's exactly what you said this. So in a moment of kind of private vengeance, he'll be marked for life. Or he may be able to go and live in Nantucket or somewhere in New England where Christopher Walt's character wants to go, but he's going to have this mark upon him.

00;46;29;00 - 00;46;51;25

Renana Keydar

Yeah. And I think that's really also, you know, in narrative wise, it's really we said already that the two plots converge in the cinema, but he really the plot has a closure, right? Because it starts with something that Shoshanna and her private pursuit of vengeance that does not reach a closure in the sense that she's dead before she knows what happened to all the other criminals.

00;46;51;27 - 00;47;33;07

Renana Keydar

And now it's like this final last revenge that really closes in a way, closes the film, closes the two plots. I want to say something else. As I said in 1961, when Iceman is caught, Israel is not thrown into a wave of revenge. And that's telling. When Israel is thrown into the air. In a way, the rules of revenge is when people, Holocaust survivors in the 1950s start to identify their fellow inmates in a way or, you know, a concentration camp, couples in the streets of Israel, in the street in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, Haifa.

00;47;33;10 - 00;48;05;25

Renana Keydar

And that's when they demand revenge. And they go to their legislators, they go to the police, and they demand a law that will enable them, well, not to shoot these, the collaborators in a way, but to put them on trial. And you see here how the public and the personal all really melt together in a way. And I think this kind of, this personal need for closure, this a bit goes to personally hurt you is very, very strong both in real life and in the cinema.

00;48;05;25 - 00;48;10;12

Renana Keydar

So that's why this thing, you know, it's very powerful to me.

00;48;10;14 - 00;48;22;29

Jonathan Hafetz

Well, Renana, I want to thank you so much for coming on the podcast and talking about Inglorious Bastards and International Justice and all of these themes around narratives of progress and their limitations.

00;48;23;02 - 00;48;28;18

Renana Keydar

Thank you very much, Jonathan, for having me. It's always a pleasure to speak to you and definitely to speak about, you know.

Further Reading

Hussain, Nadine, “‘Inglorious Basterds’: A Satirical Criticism of WWII Cinema and the Myth of the American War Hero,” 13(2) Inquiries Journal 1 (2021)

Jackson, Robert H., Opening Statement before the International Military Tribunal, Robert H. Jackson Center (Nov. 21, 1945)

James, Caryn, “Why Inglourious Basterds is Quentin Tarantino’s Masterpiece,” BBC (Aug. 16, 2019)

Keydar, Renana, “‘Lessons in Humanity’: Re-evaluating International Criminal Law’s Narrative of Progress in the Post 9/11 Era,” 17 (2) J. Int’l Criminal Justice 229 (2019)

Kligerman, Eric. “Reels of Justice: Inglourious Basterds, The Sorrow and the Pity, and Jewish Revenge Fantasies,” in Quentin Tarantino's Inglourious Basterds: A Manipulation of Metacinema (Robert Dassanowsky ed., 2012)

Tekay, Baran “Transforming Cultural Memory: ‘Inglourious Basterds’”, 48(1) Film Criticism (2024)

Renana Keydar is an assistant professor of law and digital humanities at the Hebrew University, where she also is academic director of the Center for Digital Humanities and heads the Alfred Landecker Lab for the Computational Analysis of Holocaust Testimonies Professor Keydar is the recipient of the prestigious Alon Fellowship for outstanding young researchers. She holds an LLB in law and a BA in political science from Tel Aviv University and a doctorate in comparative literature from Stanford University. Professor Keydar was a post-doctoral research fellow in the Minerva Center for Human Rights and a research fellow in the Martin Buber Society of Fellows at the Hebrew University. She also previously served as a legal advocate in the Israeli State Attorney’s Office, High Court of Justice Department. Among her numerous publications, Professor Keydar is the author of “Lessons in Humanity: Re-evaluating International Criminal Law’s Narrative of Progress in the Post-9/11 Era,” which uses Inglorious Bastards to explore a range of issues surrounding international criminal justice.